|

This weekend I returned to a place I haven't been in a while, but my time here change me. I spent 4-and-a-half years in New England, split between Southern New Hampshire and Boston. I moved to New England straight out of college with clear eyes and an optimistic soul. I left four years older, a little wiser, and with a new sense of purpose.

New England is part of my origin story as much as my upbringing in the rural Midwest. It is where I discovered my passion for filmmaking and storytelling. It's where my faith began to shift from textbook understandings to deep curiosities. It's where I went to film school and spent my subsequent "starving artist" years. It's where I worked a variety of jobs: pastor, wheelchair van driver, chino folder, kindergarten classroom chaos manager, high school film camp counselor. Each experience was accompanied with a cast of unforgettable characters that loved me, or at least tolerated me, and challenged me, informing my character and enriching my understanding of the world. Eventually, I felt the pull. California was calling and I had to say goodbye. I left New England, but the place stayed with me. The first short film I made while living in Boston was called "The Short Life of C.K. Rottingham." It was about the life of a prolific student film actor who never made it beyond the world of student films and the common clichés that define amateur filmmaking. He never made it "big," but he was passionate about what he did and became a legend to those who knew him. "The Short Life" is my handle on social media. It reminds me of the days where it all began; when I was broke, living in a drafty apartment just north of the Charles River, making a film about a young man who wanted to be great at his craft. My circumstances have changed over time, but in many ways I'm still that man.

0 Comments

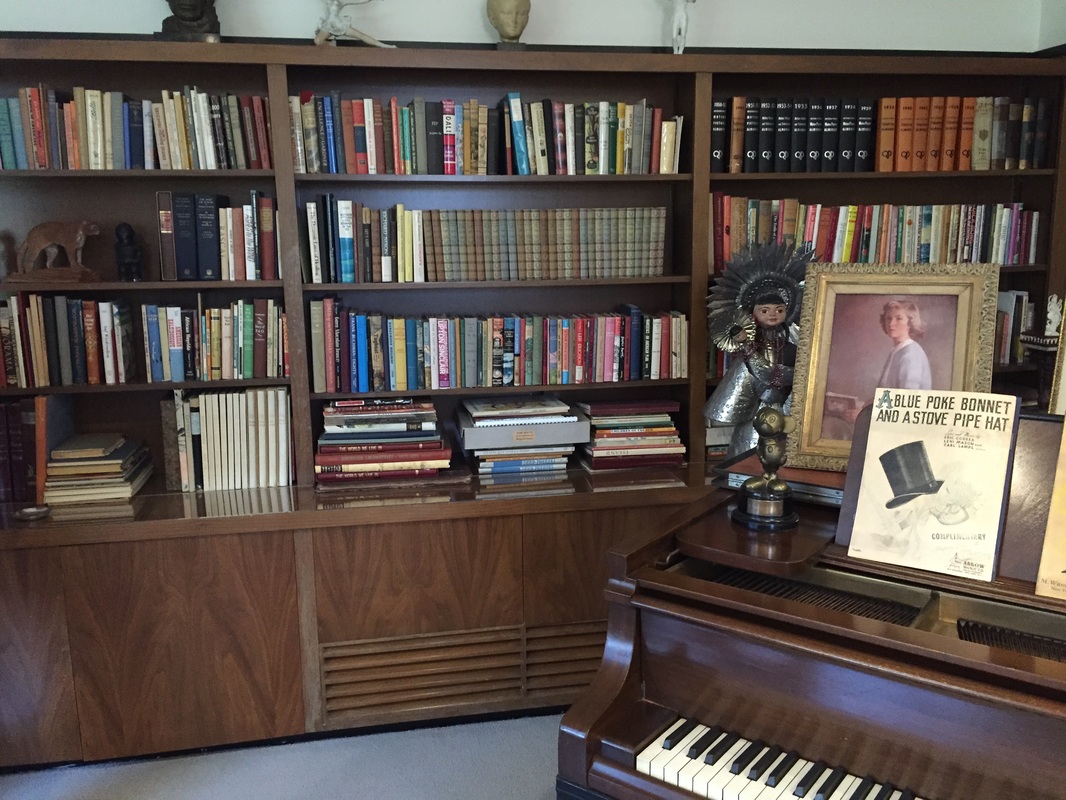

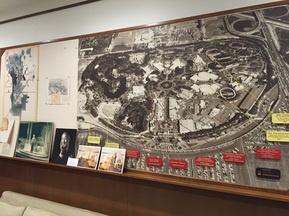

In the 1988 Chevy Chase comedy classic, Funny Farm, Chase plays Andy, a sports journalist who quits his job and moves to the countryside to write the great American novel. He sits in his idyllic farmhouse in a room with a view, a hot cup of coffee close at hand and his trusty typewriter loaded and ready. Andy puts his hands on the keyboard and… nothing happens. He peers deep into the white page. The words must be there somewhere, but his fingers remain frozen. Nothing. Writer’s Block is the condition that at its most elementary is simply “not knowing how to proceed.” The block is not unique to writers. Leaders face them. Parents face them. You can have a career block, a life block, a drunk-angry-guy-who-wants-to-fight block. When the answer to “What happens next?” is “I don’t know.” We freeze. The cursor blinks on the white pixel canvas. With each flash it taunts us: Blink. Blink. Blink. What. Are. You. Waiting. For. There are two sources of writer’s block: bewilderment and fear. Daniel Boone was once asked if he had ever been lost in the wilderness. He responded, “I’ve never been lost, but I was bewildered once for a few days.” Bewilderment is when you understand the problem, but you are unsure how to solve it. Like finding your way out of a forest, bewilderment is overcome in time with perseverance. You show up and you work toward a solution. For me, overcoming bewilderment in writing often means not writing at all. If my problem is: how do I get a character from point A to point B? And all the possibilities I’ve come up with don’t feel honest to the story, I walk away from it. Some call it “percolate” or “noodle” or “brew.” I “circle” the problem. The image of an eagle circling its prey comes to mind. I believe the answers to writer’s bewilderment are hidden in the daily routines of life: eat, sleep, shower, work, exercise. These are the rhythms of epiphany. I give my mind and imagination space to find a solution. The practice has become so familiar that I can often predict within a day or two when the solution will present itself. The second source of writer’s block is fear. You know what you want to write, but you’re afraid it’s not good enough. You may think the problem is you don’t know where to start, but really the problem is you’re afraid to start. The blinking cursor taunts you. Blink. Blink. Blink. Who. Do. You. Think. You. Are. Insecurity is the soul mate of every artist. Just this past week I heard both Steven Spielberg and Shane Black talk about how insecure they feel with every film they make. They are arguably two of the very best at their craft with years of experience and a résumé of success and yet the fear is as real to them today as it was when they first started. The only way to overcome writer’s fear is to put words on the page. You must write. Something. Anything. Every key strike is a battle cry. With each word you type you forge your way through the wilderness of insecurity. And as you do, don’t look back. The blinking cursor can’t taunt you if it doesn’t have time to rest. Walt Disney occupied a suite of offices, known as Suite 3H, on the third floor of the Animation building at the Disney Studios in Burbank from 1940 until his death in 1966. When Walt died it came as a surprise and as is common when a family member passes no one was ready to close his office and pack his belongings. His offices sat untouched and unoccupied for several years. Eventually, in 1970, a young archivist was tasked with the job of cleaning out Suite 3H. The archivist took his job seriously and meticulously inventoried every item. Suite 3H was heavily remolded and became the home to several leaders of the Walt Disney Company, including CEO Michael Eisner and Roy E. Disney. From 2008-2015 the space was leased to production companies and for a time the walls of the suite were painted bright red, a favorite color of a particular TV producer who occupied the space. Last year, Disney leadership decided to restore the offices of Walt Disney. After an extensive five-month restoration process Suite 3H was reopened as a permanent exhibit honoring Walt Disney. Using photos and the detailed inventory of the materials taken from his office, archivists were able to bring Walt’s offices back to the way they were in 1966 with an estimated 90%-95% accuracy. The paperclips on the desk are the same paperclips that sat on Walt’s desk the day he died. The offices are not open to the general public, but as an employee of the company I was able to get a tour. I found it hard to wipe the smile off my face as my imagination ran wild: the people, the conversations, the ideas that once occupied this space… Suite 3H consisted of several offices including the secretary’s office, a formal office, a working office, and a private room. The formal office was where Walt held appointments with important guests and dignitaries visiting the studio. He spent time in the office everyday answering letters from business associates and fans. It contained Walt’s prized possessions: knickknacks and gifts from around the world, Norman Rockwell sketches of his daughters, and bookshelves packed with volumes written by his favorite authors. Next door to the formal office was Walt’s working office. This is where Walt would meet his staff, including producers, writers, directors, and business advisors. Scripts and treatments for then-current projects remain behind Walt’s desk as does preliminary work on EPCOT displayed on the opposite wall. Walt’s private quarters were connected to his working office. It maintained a small bedroom and bathroom and was originally meant to be an overnight apartment, but it was rarely used for this purpose. Walt would retreat there to relax at the end of the day and, later in his life, receive physical therapy. It was there that Walt’s daughters would set-up camp and do their homework when they visited their father at the Studio. There are few pictures of the space, so today it has been re-designed to be a rotating gallery.

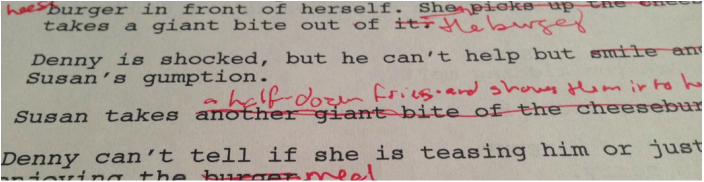

For twenty-six years these offices were home to ideas and innovations that would span the globe. It feels right that the space be restored to its original grandeur as an inspiration for future generations. I have experienced note sessions more painful than breaking up with a girlfriend.

A note session, for those unfamiliar, is when you muster the courage to put your ideas on paper, you spend hours writing and re-writing, wordsmithing and crafting, then you take your story to a group of people and say, “What do you think?” I’ve sat through hours of note sessions over the years, either giving notes or receiving them, most in the context of a writers group. They are incredibly valuable, but can also be, at times, painful. Your story is your baby and you really want people to love your baby. So when they start pointing out your baby's flaws, it can be an unpleasant experience. Here’s the thing: if you write a script and you don’t listen to any notes you receive, the end result will be a bad script. On the other hand, if you write a script and you try to implement every note you receive, the end result will also be a bad script. I’m convinced that receiving notes and knowing how to apply them is a skill that must be honed with practice. Here are few things I’ve learned over the years: Find people you trust. Note sessions are useless if the readers are not going to be honest with you. So giving your script to a curious friend probably isn’t going to do you much good. They’ll tell you they liked it. You need to find people who you trust to tell you the truth. Paying a service for an anonymous evaluation may be worth the investment if you don’t feel you have those honest voices in your life. Listen. Listen. Listen. Don’t be defensive. It’s amateur. Be grateful. They could have been reading Shakespeare, but instead they took time to read your work. Conserve your energy for the rewrite instead of arguing with the reader that they just don’t “get it.” Beware. Not all notes are good notes. Some people will give you all sort of ways to make your story, their story. Good notes will help you tell the story you want to tell. Look for patterns. If you’re not sure where to begin, start with the most consistent feedback. If two people commented that they were confused in act one, even if it is not at the same point, then you have an act one problem. Start there. Get back to work. The note session may reveal that you have a lot more work to do. This can be disheartening. If you need time to lick your wounds, put a clock on it. You have 24 hours to sulk. When the time is up, get back to work. Treat yourself to Ice Cream. Feedback is part of the creative process. Yes, it can be painful, but it is absolutely necessary. Embrace it. Don’t fight it. When it’s over, treat yourself to some ice cream and tell yourself, “You’ve made it this far. Don’t stop now.” |

AuthorA WRITER AND TRAVELER KEEPING THE FAITH IN LOS ANGELES Subjects

All

Archives

August 2022

© 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed