|

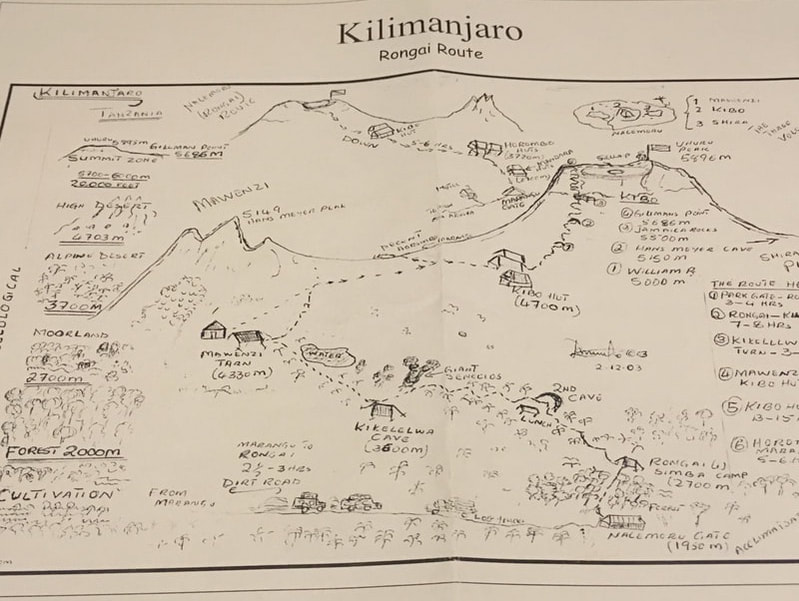

A hand-drawn map given to us the night before our trek began. What to say? I’ve been pondering what to write about the mountain since I returned. We’ll start with the facts. It was a 49-mile trek up and over the world tallest freestanding mountain. We took the Rongai route to the summit, a drier but less popular route because of its starting location on the north side, the Kenyan side, of the mountain. It took four days to reach the summit. We trekked through diverse climate zones including rain forest, moorland, alpine desert, and artic. It was cold at the top, especially at night, wind chill around 0 degrees. There were 21 people in our group. 17 reached the crater rim. We descended the mountain on the Marangu route, a popular route on the southeast side of the mountain. A crew of 75 guides and porters assisted us at varies times along the way. Those are the facts, but the experience is something I’ll be thinking about for the rest of my life. Mornings on the mountain began with a guide knocking on our tent and a choice of tea or coffee - a hot drink to enjoy in our tent while our bodies woke to a new day. The guide would return later with “washy washy,” a bowl of warm water for which we could try to maintain some semblance of hygiene. Around 7am a breakfast consisting of porridge, bread and jam, eggs, and fruit was served in the mess tent. After breakfast, we packed and set-off for the day's journey. I carried a daypack with three litters of water, extra clothing layers, snacks, and essentials, like sunscreen. My duffle bag, which contained the rest of my gear, was carried by a porter… on her head. The stamina the porters demonstrated was remarkable. They did everything we did (except for the summit) only much faster and with a heavier load. When we reached camp in the afternoon, our tents were set-up and ready for us, and a snack of popcorn and hot tea awaited in the mess tent. The operation was seamless. It made the time on the mountain not only bearable but also enjoyable. Mountain living, it turns out, wasn’t so bad (except for the not showering for days and having to use a toilet tent). For the first couple days, the pace was excruciatingly slow. “Pole pole” (pronounced poll-e, poll-e) the guides would implore us. “Slowly Slowly” It is how you acclimatize to the mountain. It is how you reach the top. By day four, they wouldn’t have to remind us to "pole pole." The most challenging days of the trek were days 4 and 5, which felt like one long day. On day four we walked 5 hours across the barren wilderness called “the saddle.” It was a moonlike landscape of dirt and rocks and few hardy floras. The views were sweeping, the distances deceptive. The winds howled, piercing our wool and nylon layered defenses. It was a taste of what was to come, but we didn’t know it yet. We arrived at Kibo Hut, base camp, early in the afternoon. We ate lunch and then were sent to our tents to rest for the afternoon. We would make our push to the summit that night. At dinner, we learned that one of our fellow trekkers would leave the mountain immediately because of altitude sickness. Struggling the last couple days with nausea, headaches, and fatigue his condition was not improving. He had become incoherent, and a blood/oxygen reading had indicated that it was serious. They gave him emergency oxygen, put him on a stretcher, and three guides rushed him to a camp at a lower altitude. There, a vehicle would take him to a hospital where he could be monitored by doctors. Fortunately, he would be fine. Once off the mountain and at a lower altitude he returned to his usual self. That’s the thing about altitude sickness; you never know how it’s going to affect you. Age and fitness level have little to do with it. I was fortunate. I experienced only minor effects from the altitude. After dinner, we returned to our tents to rest. I was restless, wondering camp, snapping pictures, looking up at the snow-covered carter. I spoke to one of the guides who implored me, “My friend. Please try to get some rest.” I heeded his advice and returned to my tent and tried to get some sleep. At 11pm the guide knocked on our tent. It was time to go. We met in the mess tent, where they tried to feed us again, but nobody had much of an appetite. At midnight we lined up, headlamps blazing, and began our slow march up the crater wall. I’ve been asked why we started the final ascent in the middle of the night. I’m not entirely sure, but I think it is a combination of factors. The weather is more predictable. It provides the opportunity to see the sunrise from the peak. It saves time, only needing to spend one night at high altitude base camp instead of two. But I think a primary reason is that in the dark, you can only see what’s right in front you. It forces you to stay in the moment, one foot in front of the other. I wore five layers over my torso: a long-sleeve polyester base layer, a wool sweater, a synthetic down jacket, a zip-up fleece, and the water-resistant windbreaker. On the bottom, I wore a pair of leggings and thick hiking pants. Covering my head was a wool skullcap and a thicker stocking cap. I was cold. Very cold. Though I was wearing gloves, I had to limit the use of my trekking poles because they exposed my hands to the elements. When we were moving, the cold was uncomfortable but tolerable. When we stopped for a short rest, my body started shaking. At one point, I asked a fellow trekker if we could cuddle for a few minutes and share our body heat. This was the challenge of Kili, different from any other endurance challenge I’ve faced. It was not the fitness required that made it difficult. It was the fatigue and the cold, intensified by labored breathing in the thin air that tested my mental fortitude. There was a moment about halfway up the seeming never-ending switchbacks that I thought to myself, “Man was not made to be on mountains like this.” Yet there I was. I could hear the sound of my fellow trekkers pausing to vomit. Feeling better, they got back in line and continued on their way. Our guides were wise. At just the right moments they would sing, all of them, in harmony. They sang in English and Swahili, old hymns and spirituals and the occasional pop song. Their voices lifted our spirits. At times, it was a transcendent; my body trembling in the wind-blown cold, my mind wavering between determination and doubt, the infinite depths of glittering night sky blanketing us from horizon to horizon, our guides singing to us Leaning on the Everlasting Arms. I’m near the lead guide when calls out, “Do not give up. I can see the top!” I knew we had to be getting close. The horizon was glowing. The sun was about to make its appearance. After five-and-a-half hours, the long journey into night was almost over. There was a release of emotion when we stepped onto the crater rim at Gillman’s Point. Each person arrived to hugs and tears. Our guides poured cups of hot tea to revive us. The joy of reaching this point, of no longer climbing in the darkness, was euphoric. The sun broke the horizon, and I got my first peek into the snow-covered crater. I will be a sight I never forget. The thrill of the moment was short-lived. The realization dawned that we were not finished. We had summited the crater rim, but Uhuru Peak, the highest point on Kili, at 19,340 feet, was on the opposite side of the crater rim. We still had a ways to go. If I’m honest, I could have been talked out of continuing. It felt like an accomplishment getting to where we were. Some did choose to head down at that point, but 11 of us soldiered on. The path of gravel and rock turned to snow and ice about a third of the way. And though the sun was up, the cold and wind had not relented. We staggered forward. Each step was a grind. It took another 90 minutes, but eventually, we looked up and saw the signpost. “Congratulations. You are at the Roof of Africa.” We waited for our turn to take pictures. I put a smile on my face. Our group crowded together to document the moment. Once the cameras were down, we turned to our guides and told them to get us off this mountain. The descent was fast. It took about three hours. Most of the time made up by avoiding the switchbacks and sliding down the long scree slopes. It was skiing with our feet, a tiring exercise for the legs, but much faster. And we were down for faster. I arrived back at my tent mid-morning. The summit trek had been a 10-hour ordeal. Out of the wind into the warmth of my sleeping bag, my body rested, and my mind tried to process what just happened. Our hiking for the day was not over. We ate lunch at around 1pm then set-off for a three-hour hustle to our camp for the night on the south side of the mountain. There we were able to sit in the warmth of the sun, out of the wind, and at a lower elevation. The white-capped rim visible in the distance, I kept thinking, “I was there this morning.” The next day, we experienced the ritual tipping ceremony. Our guides and porters sang songs, and in the form of tips we thanked them for sharing their mountain with us and expressed our gratitude for their kindness and help. The tips were divided among the crew allocated to individuals based on their responsibilities. We ended our trek with a 12-mile descent through beautiful moorland and rainforest. I couldn’t wipe the silly smile off my face when I turned the corner and saw the gate exiting the park. It was over. Our time on the mountain had come to an end. We bought cold beers at the gift shop and toasted to our time on the mountain. A lager never tasted so good. It has been nearly a month since I was on Kili. I’ve thought about it every day. I’m reminded of something Jesus said about faith that can move mountains. In my experience, the only thing moving mountains is the massive tectonic plates beneath the earth’s crust. Perhaps he meant that with faith you can move through mountains. You can transcend the immovable obstacle, ascend to its sun-kissed summit, and feel the Spirit alive in you once again. That is the power of the mountain. That was Kili for me.

0 Comments

|

AuthorA WRITER AND TRAVELER KEEPING THE FAITH IN LOS ANGELES Subjects

All

Archives

August 2022

© 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed