|

After several days of gazing at the backside (the western side) of the Grand Tetons, I was anxious to get a closer look. Leaving Idaho and crossing back into Wyoming, I stopped for a short 5-mile hike in the meadow rich Jedediah Smith Wilderness. Bear spray on my hip, I was ready for anything, but the wild was calm. The hike was peaceful, and my only encounters were a few people, a couple of dogs, and the remnant flowers from the spring bloom. A view from the valley in the Jedediah Smith Wilderness After the hike, I stopped in Jackson, Wyoming, for lunch and hopped on a Zoom call for work. With a full belly and my work responsibilities behind me, I continued my drive north. I stopped several times to take pictures and bask in the stately wonder of the jagged alpine peaks and soon realized I had shorted myself on time. A few hours is not nearly enough time to take in this iconic and aptly named "grand" mountain range. (Whether "Teton" is aptly named, I'll let you decide for yourself.) It is stunning to behold, and I longed to be swallowed by the view, consumed by the wonder of these heaven-reaching pyramids of stone. A view of the Tetons, snapped along side the road. Yellowstone was the reason I left LA on this road trip. In the COVID climate, the great outdoors was one place that still felt safe, at least from the virus. I had never been to Yellowstone, but I've felt drawn to the site for many years. Knowing that Yellowstone was in my own proverbial backyard, I assumed I would get there someday and choose to travel internationally when I could. Unable to travel abroad this year, I could no longer resist the pull that Yellowstone had on me. The time had come. All other stops on this 40-day road trip were in service of my eventual arrival to and return from Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone is extraordinary, and I write that without hyperbole. The park is so many things that it is difficult to describe. It is grand waterfalls and deep canyons. It is thick disorienting forests and wide expansive plains. It is thrillingly close wildlife and otherworldly geothermal activity. When you see the exploding geysers, the bubbling hot mud, and the steam leaking from fissures in the ground, you can't help but feel the eerie premonition that this whole place might erupt right beneath your feet. If it wasn't all so wonderful, it might actually be frightening. My cabin was in the Canyon resort area of Yellowstone. The place was not a rustic log cabin like one might imagine; the bed was soft, the water was comfortably hot, and the electricity was reliable. It's what the place did not have that made the difference. There was no TV and no wifi, and I was lucky if I got a single bar of cell phone reception. I could not retreat to the cabin at the end of the day and engage in the artificial company of a television show or distract myself with social media. There was no way to drown out the whispers of the soul by escaping to the mundane entertainments. My options were to read, write, or listen to music; each required a kind of slowing down that confronted my perpetual restlessness. On the second night, I went for a drive, looking for a quiet place to watch the sunset. I found this rise above a small pull-over on the side of the road. I climbed the mound and saw the serene Yellowstone River wind through a golden valley, loons bathing in the shallows, and mountains silhouetted in the distance. A herd of buffalo on the opposite side of the road attracted fellow sight-seers' attention, so I had the spot to myself. I found a place to sit on the highest point of the overlook. I sat cross-legged and took several deep breaths.

A tremendous sense of gratitude swelled in me. The disappointment and anxiety that lead me on this trip melted in the sight of the simple beauty and the wild elegance. I had not heard from God in a very long time. Years ago, God was my companion. He was with me in conversation and had much to say. I had confidence that the Great Father had a plan for my life, and we often discussed how the plan was going. I sang songs to God. I felt a lot of guilt over my failings. But over the years, the voice of God faded. It went from a resounding voice to a subtle whisper. Then, it vanished altogether into silence. Above the Yellowstone River with the reflection of the sunset dancing on its glassy surface, I thought, "Well, here I am, Lord. If you have something you want to say to me, now is the time. I'm listening." Silence. I took several deep breaths. I repeated. "Here I am. I'm listening." Silence. The Voice of God was absent. However, I felt a presence come and sit beside me. I again said. "If you have anything you want to say to me, I'm listening." Still silence. No words of assurance. No directions for what to do next. No explanations for why life was the way it was—only God's presence. In that moment I realized, my faith in a God that is "up there" or "out there" somewhere, speaking its will into my life, was dead. There was no going back to that God. I felt that in the deepest way. Instead, a God that is here beside me, above me, around me, in me; a God in which I live and move and have my being has risen in its place. This God of beauty, God of mystery, has little to say. No instructions. No explanations. No messages. No certainties. No affirmations. No judgments. It offers only its divine and transcendent presence. A few simple words began to impress upon my heart, not from a voice from above, but from a place deep inside my being: Abide in me. Abide in my love. The whole experience lasted, I don't know how long, maybe 30 minutes? I got what I came for, but not what I expected. I met God, and it was Silence. A peace that surpasses understanding filled my soul, and a smile of sweet surrender graced my face.

1 Comment

A view of the Oregon Trail along the Wyoming/Utah border. After visiting Zion National Park, I spent the next week in Park City, UT. The outdoorsy lifestyle of this small town nestled against the Wasatch mountains provided a perfect place for realigning with my new unsettled life. In the mornings, I explored local trails or sat outside on the deck of my Airbnb and read. In the evenings, it was more of the same. Not knowing anyone in the area, I had to set aside my introversion and practice my cringe-worthy small talk skills with locals. My eagerness to connect with someone prompted an overniceness and willingness to chat. However, after about ten minutes of conversation, the exhaustion set in, followed by the panic of having no idea what to say next. I had to remind myself that I encouraged this conversation, and I had to stick with it. After Park City, I headed north to Idaho. Abandoning the freeways and interstates for two-lane highways, I finally felt as if I was truly getting away from the constant noise and frenzy of life (yes, even life in quarantine can be filled with noise). A repetition of yellow warning signs featuring silhouetted wildlife and messages of free-range cattle added to the sense that I was somewhere new. There is both a thrill and discomfort that accompanies this feeling. Leaving the comfort of familiarity behind and stepping into the tension of the new, one becomes open to possibility. After stopping for a world-famous raspberry shake in Garden City, UT, I crisscrossed the Utah/Wyoming/Idaho border for miles following the famous Oregon Trail. Progress was slow as I discovered many "I've got to get a picture of this" moments as the highway rolled through hidden valleys and opened to mountain vistas. Back in LA, where time and convenience were of the essence, I could open my gated car garage with the click of a button. When I arrived at my Airbnb, a sturdy home on the Teton County plain, four sheep lay in front of the gate. My instructions said to "shoo" the sheep away, open the gate, and come on in. I hopped out of my car and approached the lounging animals. The sheep stared at me, and I stared back at them. After some coaxing and clapping, followed by a fit of pleading, the sheep moved off the drive, and I pushed open the gate. Two dogs ran toward me, tails wagging, eager to welcome their new guest. I drove through the gate, hopped out of the car again, and swung the gate closed, careful not to let loose any animals. "I can relax now," I thought to myself, "no one here is in a hurry." When I met Andy, my host, he offered his hand. I hesitated, then shook his hand. His was the first hand I'd shaken in the five months since the pandemic began. "Should I wear a mask?" I asked. "Nah. Unless you feel like you need to," was his response as he led me into his home. The pandemic—or the concern over COVID—had not reached this corner of the world. I met two young travelers, Fernando and Esther, coincidentally also from Los Angeles, working remotely, as I was. I welcomed the company. We laughed together one evening as Fernando (of Asian and Latino descent) recalled as a child the day that he realized he wasn't white. Esther charmed Andy into taking us flyfishing, a first experience for all three of us. On the second night, Andy shared his story. He served three tours in Iraq. This house he built near the Tetons was his "therapy." He became overcome with emotion telling us about the nonprofit he started to reunite retired military dogs with their handlers. "Those dogs saved so many lives… it's only right." He described the pure, tearful joy when a soldier reunites with his or her dog. In Andy, I saw a man working with the shadows in his soul. He was a good man who cared deeply about others while doing his best to reconcile his personal suffering with a desire for inner peace. Andy epitomized the American ideal of self-determination. A hard-working kid from North Dakota, he joined the military, where he got into technology. After his service was complete, he consulted, then started his own businesses and found success and a livelihood. He designed and built his own house, which he (and his wife) opened to travelers from across the world. It's a place where people like me can sit outside and watch the sun drop gloriously behind jagged mountain peaks while swapping stories with one another. This is America at its best. When hospitality softens ideological divides. When our shared humanity triumphs over politics. When three Californians can sit on an Idaho man's porch laughing and crying about the surprises, joys, and struggles of life. The moon rises over the Teton mountains. The American flags waves proudly in Andy's front lawn.

Leaving Los Angeles, I found myself in the barrenness of the Mohave Desert. It was an appropriate place to begin my journey. Isolated in an apartment for months, the walls felt like they were closing in; each day the jaws of a claustrophobic vise-grip twisted tighter. In addition to the heaviness of the world’s crises, I was working through another failed relationship. Its confusion and disappointment weighed on me like an anvil pressing on my soul. I was empty; spiritually, emotionally, and mentally. I needed distance and space. I needed to drink from the well of some other place. I wanted to go somewhere, but where? I looked at my wall map. My eyes kept returning to a space in the US I had yet to explore: the American West. It didn’t take me long to decide that it would be the place of my wandering. The West remains a mythic space in the psyche of Americans (and the world). And though the vast wilderness may not be as wild and undiscovered as it was in the 19th century, symbolically it is still a place for journeymen and women. It is still a liminal space for the adventurer, the gold-seeker, the one searching for new life. But first, the desert. As I drove through the dusty and parched landscape, the temperature hovering around 110 degrees, questions of uncertainty whispered in my mind. Would forty days of solo travel compound my feelings of isolation and loneliness? What if my vehicle was not up to the task? What if I got COVID? How would I take care of myself? What if I spread COVID? Is this trip reasonable or selfish? Doubt sat next to me in the empty passenger seat as I passed miles listening to Dune on audiobook. I gazed out the window. I was on Arrakis. I arrived at my first stop, an Airbnb in Toquerville, UT, and settled in for the night. The next morning I woke pre-dawn, and I got my first glimpse of the many wonders I would see on this trip. Winding up Route 9, the cliffs of Zion National Park rose around me. The 2,000-foot rust-red walls towering to my left and right stood in contrast to the green foliage springing to life around the Virgin River. This is what I imagine the Garden of Eden would have looked like. I realize I’m back at the beginning. I get a glimpse of paradise, before the separation, before all the brokenness. The breeze tingles my face as a smile appears on my face. My thirst subsides for the moment. Route 9 winds through Zion National Park The magical landscape of Zion

The car is packed. I’ve kicked the tires. And I have more trail mix than one man can possibly eat. I’m soon leaving Los Angeles for six weeks on a solo road trip through the iconic and mythic American West. Utah. Idaho. Wyoming. Montana. Colorado. Utah. Then back to California. That’s that plan: to return in time to start my fall semester of school. It turns out to be, exactly, a 40 day wandering in the wilderness.

I’m not disconnecting completely. During this pandemic, I’ve been working from home, and there is no sign of returning to the office anytime soon. So I’ve decided to take advantage of this unique “work from anywhere” time by hitting the road for a good long time. I’m traveling solo, and staying at Air B&Bs along the way. I’ve planned the trip in such a way I can continue to work remotely while getting a long break from the glimmer and madness of Los Angeles. I’m leaving it behind for time in the desert, in the mountains, and in the wide-open spaces that allow a person to think, feel his smallness, and perhaps crack open the rusty vault of a weary heart. The philosopher Martin Buber said, “All journeys have secret destinations of which the traveler is unaware.” I believe this to be true. The purpose of travel is not to see the expected. It is not to tick the boxes on a Rolodex of waypoints. The purpose of journey is to step across the threshold of the ordinary and enter the unknown, a place that is elusive while living in the comforts of everyday life. It is about the dumbfounding of one’s ego and the awakening to something other. Why am I going? I’m not entirely sure. It feels right. It makes sense. I’m too proud to admit that it may be a reaction to a culmination of disappointments or some sort of middle-life crisis. Or perhaps I’m simply bored. But these explanations are far too simplistic and do not account for the complexity of a soul’s longing. I don’t believe travel needs an explanation, for the journey is reason enough. As I’ve been preparing for this trip, I’ve been pondering this poem by Rilke: God speaks to each of us as he makes us, then walks with us silently out of the night. These are the words we dimly hear: You, sent out beyond your recall, go to the limits of your longing. Embody me. Flare up like a flame and make big shadows I can move in. Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final. Don’t let yourself lose me. Nearby is the country they call life. You will know it by its seriousness. Give me your hand. Rainer Maria Rilke Book of Hours, I 59 Above a field near a deep royal bay,

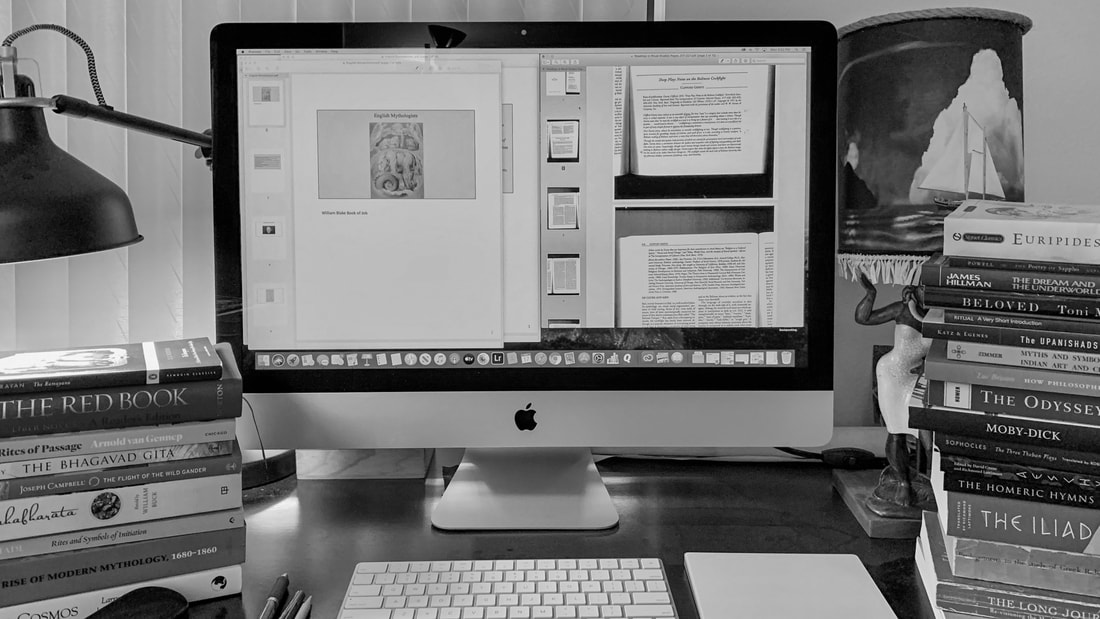

A kingdom of birds flew, frolicked, and played. In this sky kingdom, were birds of a feather, Blue birds, red birds, some even looked heather. The blue feathers ruffled the square feathers’ tassels, Left feathers rumbled with right feather rascals. Gray feathers warbled of bright feathers’ whistle, Bright feathers squabbled at green feathers’ bristle. Though grumbles and sighs and prickles and cries, All birds held faith in the song of the sky: That all birds, all birds, have a right to fly. Among the birds, there was a special lot, Long feathers were game from every flock. Long feathers soared to a song of their own, To serve and protect flights of the kingdom. Behold, the long feathers. The hardest job of all. They are brave. They are noble. They answer the call. But alarmed word spread with tales and utters, That wings of red birds were clipped by long feathers. “How could this be?” Barked the birds of a feather. “It doesn’t make sense. Long feathers don’t fetter.” So chose many birds to ignore the sad plight. “Those red birds don’t get it, don’t put up a fight.” Yet more birds tumbled, and aloud they cried, “It’s true. Look! Another red bird can’t fly.” “No!” Said the square feathers. “Red birds don’t get it.” Follow their orders, and you won’t regret it. “Rules and flight orders,” the red birds declared. “What good do they do if they are not fair?” “Stay in your lane!” Privileged feathers retorted. “This fury is ugly and makes you revolted.” Anger, it deepened, for no one was listening, The kingdom divided with all feathers quibbling. For no one could guard against fear and distrust, It grew and spread until the kingdom went bust. Trees were uprooted, and bushes defrocked, Red birds screamed, “this injustice is a crock.” We fly and we fall while our tears we must dam, Enough. Enough! No more timid as a lamb. Sadness came, but still no understanding, Just shouts and points and further dividing. Till one day a long feather flew to the middle, Removed his long feather with offer to settle. I am here, will listen, I will not ignore, For justice, I make the first step to restore. A red bird joined him, in the act of accord, “This hurt runs deep, and will be hard to explore.” The red bird, she pointed to ghosts in the sky, “Can you see? Can you hear? Do you feel their cry?” “I can’t fly.” “I can’t fly.” “I can’t fly.” “I see. I get it. We’ll make rules to fix this. So please, settle down and stop all this protest.” “Rules? Yes! But no. It must go far beyond that. Empathy. Conversation. Transformational act.” “Break bread. Walk beside. Listen to our stories, Breakthrough. March forward. And demand just juries.” “Justice is action, a revolution of the heart, Be still, be uncomfortable, find unity through art.” “‘Love thy neighbor’ He said, is not a suggestion, It’s a command to obey, without apprehension.” The long feather, he paused, not sure what to say, The red bird proposed, “fly together this day?” Up they soared, towards heaven, the wind lifted them high, A new era was born in that wide open sky. “You are right. It is ugly and painful to admit. For so long, for too long, we’ve lain complicit.” “Frustration today, with heartache and tears, Come love. Come peace. Come justice all year.” All birds of a feather watched the two glide, Together, they flew, with nothing to hide. Behold, the long feather, the hardest job of all, With humility and action, you answered this call. The books are piling high, and I've only just begun this new academic journey. After much deliberation, I decided to go back to school this past fall to pursue my Ph.D. in Myth Studies. I've been courting the Mythological Studies program at Pacifica Graduate Institute for the past few years, but the timing was never right. Last summer, I felt that urge, the call, that this is what I needed to do.

That call, that instinct, that voice was the same feeling I had when twenty-two years ago, I decided to study for the ministry. It was the same call I heard when four years later, I stepped away from vocational ministry to attend film school. It was the same feeling I had when I decided to move my life to Los Angeles 15 years ago. I had not heard her voice in a very long time, but last summer, she returned with her gentle yet persistent and familiar encouragement, "go." All the rational objections surfaced in my deliberation. This is going to cost me a fortune. It will take at least five years to complete, and in the end, there is no obvious return on investment. I mean, assuming I'm able to complete the program and I'm awarded the degree, what does one do with Ph.D. in Myth Studies? Teach, maybe? I'm not looking for a new career. Disney has been good to me. So why am I doing it? Curiosity could be a reason. I enjoy learning new things, especially on a subject matter that I find so fascinating. I love story, and doing a deep dive into the myths, stories, epics of the world is exciting to me. The sense of accomplishment might be another reason. I like things that are difficult and feel a bit impossible. I find enticing the tasks that require focus and dedication over a period of time. Creative inspiration is another reason. I've struggled over the past few years to write truly original stories. I've been in a creative drought, uninspired, trying to find something to spring my imagination to life. But I don't think any of those reasons fully satisfy the question of why. The simple yet more mysterious answer is because I felt that if I didn't do this, I would be ignoring the call. I wouldn't be doing what I'm supposed to be doing with my allotted time here on earth. Honestly, I don't know what will happen at the end of this, and I'm okay with that. I don't need to know. "Go," the Spirit beckons and have faith in the journey. The destination will reveal itself in time. So every 4-5 weeks, I drive up to the school, near Santa Barbara, for three full days of classes. The rest of the work is done at home. The biggest challenge has been finding the time to complete my school work while working a full-time job and trying to maintain a semblance of social life. I'm figuring it out, and I'm getting used to the new norm. But most importantly, I'm beginning to feel that spark again. The Myth Studies program is built on three pillars: comparative religious studies, classic art and literature, and depth psychology. I'm through one term of classes, and I'm halfway through my second term. So far, I have no regrets. The content has been a lightning bolt to my storytelling mind and has enriched my soul. My cohort is comprised of smart and insightful people from diverse walks of life. I'm already thinking of dissertation subjects and mentally preparing for the work that lies ahead. I'm so glad I listened to the call. If you want to know what fear poisons the soul of a people and plagues our collective thought, you look at the villains of our stories. Our heroes tell us who we aspire to be. Our villains tell us who we are. Mary Shelley’s classic Frankenstein was published during the golden age of the enlightenment. It tells the story of a monster that we created, not a supernatural being, but a human-made being forged from the fire of our new-found scientific knowledge. Less than 10 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Godzilla made its debut in Japanese cinema. It told the story of a sea monster from far away that breathes fire and can lay waste to entire cities. The monsters and villains of our stories reveal our deepest anxieties. Perhaps there is no villain as iconic in pop culture as Joker. In TV and Film, the sociopath clown-face supervillain with no superhuman abilities scourges the people of Gotham City and in doing so, reveals a lot about who we are.  Joker as Menace I grew up watching reruns of the 1960s Batman TV series as a kid. I loved the show. Episodes would end with Batman & Robin in a pickle, and I, for the life of me, could never figure out how in the world they might escape. Surely they will be eaten by sharks! Surely the laser beam will slice them in two! Oh the humanity! My anxiety was short-lived. As sure as the sun rises, the capped crusader found a way to escape the malicious clutches of his nemesis and restore justice and order - usually by returning the stolen painting to the museum. It was the 60s, communism was the enemy. In the struggle of ideologies, the lines were clearly drawn. We were the good guys. They were the bad guys. Good always prevails. The Joker of the 1960s wasn’t more than a menace and a prankster whose nefarious schemes were short-lived. There was no stopping the righteous crusade.  The Joker as Mob Boss Joker showed its funny face again in Tim Burton’s 1989 film Batman. I was 10-years-old, I remember the line of people that stretched around the block of my local two-screen theater. I thought this movie must be really important. It looked like everyone in town was going to see it. The collapse of the Soviet Union in the latter half of the 1980s shifted our focus from the enemy abroad to the enemies within. In America, urban crime rates reached their pinnacle. It’s no wonder, In Batman, the Joker evolved from prankster to gangster. The charismatic character became the ultimate mob boss. His gang of thugs blighted the city of Gotham, mostly out of spite. Joker and his cronies represented the fear of urban life, specifically the dark alleys and shadowy corners where the good citizens fear to tread. The hero’s task in facing Joker was to make the streets of Gotham (and America) safe once again.  The Joker as Moral Ambiguity In 2008, 19 years after Batman, Joker returned to cinemas in the second film in Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, The Dark Knight. This Joker, however, is not interested in being a gang leader or in the accumulation of money or power. His desire is the destruction of Batman himself, the icon of moral authority. Joker’s goal is to expose Batman (literally, “take off your mask”) and the fallacy of moral objectivity. By forcing our hero and the citizens of Gotham to make choices about who lives and who dies, the self-righteous lines we draw - we are good/they are bad - become unrecognizable. It is clear that Joker is a bad guy, but the people of Gotham (and the story’s audience) are left questioning: are we as morally right as we think we are? This was the question of the time. After the horrific events of 9/11, we thought we had the clear moral objective to bring to justice those responsible and to never let anything like it happen again. But seven years into the seemingly unending occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan, we were asking who exactly is the bad guy? We thought we knew. We thought we were justified. But our pursuit of the phantom ideology that hid in caves and exposed itself violently in public spaces came at a cost - in the lives of our soldiers and innocent civilians - but also in our moral credibility. The Dark Knight ends with Batman on the run with the citizens of Gotham believing him to be a criminal, not the righteous hero they thought he was.  Joker as Mental (and Social) Illness This brings us to the most recent portrayal of the character in this year’s film Joker, an origin film that explores the question: how did Arthur Fleck become the supervillain Joker? Was it mental illness, an abusive home life, bullying, the breakdown of civil services? All of the above? The film doesn’t answer the question. What is most striking to me about this film is the lack of moral conflict. There are no “good guys.” The “haves” are bullies to the “have nots” thus, they have no moral authority to stand in opposition to the cynical worldview of Arthur Fleck/Joker and his followers. And in Joker’s view, that means they get what they deserve. Joker is a villain for our time. Those in power have lost moral credibility. Our political leaders are bullies, not role models. The Me Too movement has exposed the abusive dark side of power. The “haves” continue to accumulate wealth, while the “have nots” struggle to keep up and live with a genuine threat that they may end up living on the streets (ahem, Los Angeles). Meanwhile, we are plagued with unconscionable terrorist attacks in the form of mass shootings. Our villain is not an agent from foreign soil but our very own citizens. Masked by the masses, we are stunned and sickened when they strike. “Why?“ We argue. Is it mental illness, broken families, a culture of bullying, the lack of social services to identify the vulnerable and potentially violent? Is it the proliferation of the tools of terror? In the film, Joker strikes chaos - and rises to godlike villainy - with the use of a simple handgun that was gifted to him. A weapon he should never have had. Like Gotham City, we are searching for a just hero. Joker does not give us that hero, but the film does foreshadow, albeit tepidly, the makings of one in the child Bruce Wayne. But the question remains, who will that hero be? What does a hero that must confront our social illnesses look like? He or she will need more than martial arts training and all those wonderful toys. The hero for our time will require a courageous humility and a “goodness” we have not seen in very long time. Note: This reflection on the Joker is not meant to be an exhaustive exploration of the character. I do not take into account the comic books, animated series, or Suicide Squad because I have not read or seen those stories.

I’m 40 years old. Let me tell you how it happened. I went to bed one night, and the next day I woke up and it was my birthday, my 40th birthday. It happened just like that. I remember my father’s 40th birthday very well. I was ten years old, and we threw him a surprise party. We knocked over a potted plant and rushed to vacuum the floor minutes before he arrived. I remember his “oh geez” reaction when he stepped onto the porch and realized what was going on. I thought he was old at the time. “Over the hill.” To 10-year-old Nathan 40 felt like an eternity away. A place veiled by the elder generation and by the mystique of adulthood. But here I am. I can see behind the curtain. The mystery of middle age that was hidden by my youthful eyes is now revealed. The man behind the curtain is a version of me that pops Advil for achy muscles and prefers not to stay out past 11 o’clock. I’m okay turning 40 because I have no regrets about how I lived the first four decades of my life. For sure, it hasn’t always turned out the way I expected, and there were times of real struggle, but it was all worth it. I traveled to the world. I met wonderful people. I’ve accomplished things I didn’t think were possible. I’ve loved and lost, and from it all, I grew into the person I am today. For my 40th birthday, I wish for wisdom over youth. In a culture that idolizes youth and beauty, embracing age and wisdom seems far more subversive. I used to swim in the shallow end where it was all splash and play, quick ins and outs, my feet always touching the bottom. Now I find my place in the more dangerous deep where the water is darker, the bottom unsure. I learn to breathe with the rips and the pulls and swells. When I swim with my eyes open the water reveals its secrets. An ode to all the days I have remaining: May I laugh earnestly, not insecurely May I love generously, not fearfully May I walk alongside, not ahead May I journey deeper, not higher May I grow in wonder, not doubt May I seek richness, not wealth May I run stronger, not faster So that all my days remaining may be grand Yosemite 2018

I recently completed a 10-week course offered by the Southern California chapter of the Sierra Club call the Wilderness Travel Course (WTC). Though I’ve done quite a few day hikes I was looking to improve my knowledge and skills at it relates to the outdoors to build my confidence to spend more time deeper in the wilderness. “Beach or Mountain?” is a common question posed to those of us living those Southern California. It is an embarrassment of natural riches to have the choice. I’m not opposed to the occasional beach day, but it doesn’t call to me like the mountains. Growing up in the landlocked prairie-lands of the Midwest, beach days were special events that only happened when we were on vacation, so I never got accustomed to having the sea be a part of my everyday life. The mountains, on the other hand, are a place that has always captured my imagination. I remember distinctly in Jr. High day-dreaming out the window of the third-floor classroom, imaging mountains in the distance. “How beautiful that would be,” I remember thinking to myself. To ancient people, the mountains were a mystical and dangerous place, a place reserved for the gods. Sacred mountains are hallmarks of religions and legends. Their proximity to the heavens made them the place where humankind would go to encounter the divine. Mount Etna was home to Vulcan, the Roman god of fire. Mount Kailash, the abode of the Hindu deity Shiva. For the Greeks, it was Mount Olympus. Moses entered the presence of God and received the ten commandments on Mount Sinai. Modern man has been on a millennia-long quest to tame the wilderness and conquer the mountains. We’ve been pretty successful at it. Thousands of people have now summited Mount Everest since Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hilary first reached its peak in 1953. Each year the list of unclimbed mountains and unclimbed routes dwindles. Yet, it is now that we need the mountains more than ever. Too much of the day, the week, the year I live with my head down staring at a pane of magic glass that lures my attention feeding me updates, opinions, photos, movies, music, and games. The more connected I am, the less connected I become. The mountain offers a remedy. Head up. Eyes forward. The breeze in my face and the warm sun on my skin. Listen to its wild silence. The WTC was comprised of 10 classroom sessions and four wilderness trips. It covered everything from equipment, nutrition, and trip planning to map & compass navigation and basic first aid. The wilderness does not adapt to you. It is wild. You must adapt to it. The course does not teach “survival skills.” It teaches you to be prepared and make good decisions so that you never need Bear Grylls’ skills to survive a trip outdoors. The philosopher Martin Buber said, “All journeys have secret destinations of which the traveler is unaware.” When I step into the wild, I may aim for a peak or spot on the map, but the true destination lies elsewhere. The dust on my boots and the sweat on my brow are simply the outward signs of an internal change - a humbling. Lost in the savage beauty of the wild unknown, I find myself. Check out Nisha's work at nishashankarart.com or IG @nishashankarart I commissioned my first piece of art. I needed a splash of color for my office wall so I asked my friend Nisha Shankar, a talented artist hailing from Vancouver Canada if she could do a piece for me that captures my love of travel and the mountains. The process took a few weeks. After meeting to chat about what I was looking for, we communicated via text message, Nisha sharing her work-in-progress and soliciting my feedback. She wanted me to be happy with the piece. I expressed what was working for me and what wasn’t, but tried to stay away from art directing. I wanted it to be 100% Nisha. In the end, we were both delighted with the result. I love her depiction of the world as a place of colorful beauty where borders bleed together. The compass rose, and the mountain range incites a sense of exploration and adventure. When I picked up the piece, Nisha told me that she names her paintings. She called this one “The Explorer” and she wrote this poem to accompany it. The Explorer

The Explorer sets off to discover great heights The mountain ahead feels a lifetime away The sweat of his palms fills him with doubt The glisten of white caps blinds his momentum But as the clouds part revealing an incandescent sun Birds sing in harmony This heavenly chime is a sign from God: It is time to awaken your heart This is only your start The path may be long but no dream is too steep For the Explorer has wisdom that can never be beat He breathes in life and ascends his climb One step at a time, one mile at a time Dawn to dusk to sunset to sunrise Mountains and hills, vast and steep Beyond what his grandeur expectations had been This is better because this is real To look down is no option His compass gives him direction Insight and assurance While the darkness watches patiently in the distance Night comes and day breaks until The Explorer reaches his peak He looks down at this Journey The path may be long but dean is too steep A map of trails and roads leads to memories and tears A gust of wind to his back, a whisper in his ear The Explorer finally listens to silence and hears: You have conquered the world. |

AuthorA WRITER AND TRAVELER KEEPING THE FAITH IN LOS ANGELES Subjects

All

Archives

August 2022

© 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed