|

The Camino takes many shapes. Here it is a narrow but well-worn path between a cow pasture and Spain's northern coast. This past April, Yesenia and I spent three transformational weeks walking the Camino de Santiago in northern Spain. I wrote this piece originally as a paper for a class in my graduate program. It is more academic than most of my posts (complete with footnotes!), but I think it is very readable. The first half offers an overview of pilgrimage in the Christian tradition and explores the fascinating history of the Camino de Santiago. My personal reflection on the experience is found in the latter half of the post. Enjoy!  Pilgrimage or the act of sacred travel, is a spiritual practice found in nearly all major religions. Jews travel to the Holy Land, Muslims to Mecca, and Hindus to Mount Kailash, which Buddhists call Mount Meru. Within each of these global religions are numerous pilgrimage paths and sites, where the faithful journey in hopes of finding healing, redemption, salvation, or simply a deeper connection with God or the divine nature of being. Pilgrimages don't have to be inherently religious, but for obvious reasons, many of the most popular pilgrimage sites have religious roots. For Christians, there have been three main pilgrimage sites since the Middle Ages: the Holy Sepulcher of Christ in Jerusalem, the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome, and the remains of the Apostle James in Santiago de Compostela in Spain. The practice of Christian pilgrimage predates the life of Christ. The bible is full of stories of God calling his people to leave their homes to journey to another. Abraham left for the land of Canaan after God called on him to do so, "Go from your country… to the land that I will show" (Gen. 12:1). Generations later, Moses led the Hebrew people from Egypt to the promised land, which included forty years of wandering in the wilderness (Exodus 2:20). Following a star, the Magi journeyed from afar to visit the infant Jesus shortly after his miraculous birth. Christ carried his cross down the Via Dolorosa, "the way of grief" in Latin. Saul's supernatural encounter with the Christ and his subsequent conversion took place while traveling the road to Damascus. The sacred practice of pilgrimage may be a reoccurring religious practice because the outward physical act of travel mirrors the inward journey of the soul towards the divine. The prophet Jeremiah writes, "Thus says the Lord: Stand at the crossroads, and look, and ask for the ancient paths, where the good way lies; and walk in it, and find rest for your souls" (Jeremiah 6:16 NRSV). New Testament writers use the language of pilgrims to describe the state of our soul on earth (Hebrews 11:13-16 and 1 Peter 2:11). It seems an essential practice of the spirit to be on the move. The act of pilgrimage stands in contrast to the perception that in order to achieve a true spiritual state, one must be in a meditative or idle position. There are times the path to God is found by walking. The great religious traditions understand this, and Christianity is no exception. The Camino's "Norte" route is mix of dirt trails, cobblestone pathways, and paved roads. Signposts with yellow arrows and the shell symbol reassure peregrinos (pilgrims) that they are on the right path. The Camino de Santiago, in English, the "Way of Saint James," is an early medieval period pilgrimage route to the shrine in Santiago de Compostela, where it is said the remains of James the Apostle are buried. The story of the Camino de Santiago is a mix of legend and church history. James was the brother of John, both of whom were two of Jesus' first four disciples. The brothers were known as the "sons of thunder" (Mark 3:13), perhaps for their fiery tempers and fierce loyalty. James was part of Jesus's inner circle and witness to miracles (Mark 5:37), the Transfiguration (Mark 9:2), and Jesus's anguish in the Garden of Gethsemane (Mark 14:33). He was beheaded by King Herod Agrippa in 44AD (Acts 12:2). This is where the biblical account of James, the son of Zebedee, ends, and church history and legend begin. The Spanish story claims that James was a missionary to the Iberian Peninsula after the death of Christ. He was not a very successful missionary, converting only a few disciples. He eventually returned to the Holy Land, where he became the first recorded martyr in the New Testament. After his death, his remains were smuggled back to Galicia in the northwest region of modern-day Spain on a sail-less boat, where his disciples, the few that he had, received his remains and placed them in a cave.1 His remains lay hidden there for nearly eight centuries. Around 813, the hermit Pelayo heard music and saw lights shining over a cave in the woods. He dug up the sight and discovered bones and a parchment, presumably identifying the remains of Christ's disciple. The bishop authenticated the site as the remains of James the apostle.2 It wasn't long before word of the discovery spread, and pilgrims began making their way to the tomb. A small chapel was constructed to guard the relics, and a small town grew up around it. The timing of the discovery was fortuitous. By the 9th century, the Moors had gained control of much of Spain. Christians in the north and northwest of Spain were desperate. The discovery of the holy relic may have empowered the Asturian army to face the much stronger Moor force, which carried their own holy relics into battle. In the pivotal and tide-turning Battle of Clavijo, which some scholars believe never actually happened, legend says that Saint James appeared on his white horse and led the Christian armies to victory.3 Word of the infamous Santiago spread. Thus, James became the patron saint of Spain serving dual roles as Santiago Peregrino, James the spiritual pilgrim, and Santiago Matamoros (James the Moor-slayer). As word spread, pilgrims from across Europe began flooding the area. The emergence of the Codex Calixtinus manuscript around the 1130s provided a list of miracles attributed to St. James, the history of the route, and advice for pilgrims, including warnings of dangers.4 The city of Compostela grew to accommodate the crowds arriving daily. All along the way we encountered signs of a bygone world. Religious markers erected in fields where livestock graze today. The door of this centuries-old stone chapel bears the marks of long ago visitors. The 11th and 12th centuries marked the period of the greatest pilgrimage activity, not coincidentally, as the veneration of holy relics reached its apex.5 The importance of iconography in religious experience during the Middle Ages cannot be understated. The majority of people were illiterate and dependent upon educated clergy to recite scripture. Hymns served to help believers remember sacred texts. Iconography filled in the gaps where words could not be read. Relics, images, and symbols became important ways for everyday people to strengthen their faith, reinforce their beliefs, and connect with the sacred. Though the medieval attraction to relics was so strong, it became superstitious for some, believing certain images were necessary for healthy living or a good harvest; for many, it was their way of experiencing God. St. John of the Cross (1542–1591) wrote about their importance: "Our Lord frequently bestows these favors by means of images situated in remote and solitary places. The reason for this is that the effort required in journeying to these places make the affection increase and the act of prayer more intense.”6 The claim that the relics of the apostle James were resting in Europe would have been irresistible for many spiritual seekers during this period. At the peak of the Middle Ages, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims made their way across Europe to Santiago de Compostela. It was a harrowing effort with no certainty of arrival. Up to the point of debarking for Compostela, most pilgrims would have never ventured far from their homes. This pilgrimage involved traveling hundreds of miles over terrain their eyes had never seen, vulnerable to all kinds of dangers—violent robbers, extreme weather, wild animals, and deadly disease, to name a few. Why? Pilgrims traveled for varying reasons. For many, the veneration of relics offered a strong pull, but so did the demands of penances. Other pilgrims may have sought healing and miracles. This is understandable considering the bubonic plague ravaged Europe during the 14th century killing one-third of the European population. In her book, Women Pilgrims in Late Medieval England, Susan Morrison notes that a large number of pilgrims were mothers traveling to shrines, often barefoot, for the healing of their sick and dying children.7 Some travelers may have desired an adventure. Whatever their reasons, scores of pilgrims during the Middle Ages risked greatly to be counted among those who made the Way of Saint James. Our journey took us through many villages, towns, and cities. On the left, we stopped to look back at the quaint seaside city of Zumaia. On the right, evening sets on San Nikolas church in Balboa (one of our favorite cities on the tour). There were critics of pilgrimage. As early as the 4th c., Jerome (c. 347–420) argued that a holy life is more important than a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.8 However, the fiercest critiques of pilgrimage in the Christian tradition came during the Reformation in the early 16th century, when Luther and Calvin argued for salvation based on faith, not works. The Protestant reformers offered a message of faith alone that warned against idolizing humans or objects or confining God's presence to particular places. This message stood in contrast to the medieval expression of pilgrimage as salvific with it its emphasis on iconography, sacred relics, and penance. During the Reformation, the number of pilgrims traveling to Santiago de Compostela dwindled but did not disappear. There were Christians who still viewed pilgrimage as an undeniably biblical practice. For example, English Puritanism of the 16th and 17th centuries recovered an Augustinian understanding of pilgrimage.9 Additionally, literary works like John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress (1678) allowed the discipline of pilgrimage to survive the Reformation. The Camino de Santiago became less popular during the Enlightenment period with its emphasis on religious skepticism, but the Camino never stopped altogether. The number of guides and memoirs written during the last half of the millennium indicate that there has been constant pilgrimage activity focused on Compostela.10 The Camino de Santiago saw a resurgence of pilgrims during the 20th century due in part to Spain's investment in making the Camino easier to travel and the rise of mass media, which spread stories of the Camino through songs, memoirs, and films. In more recent years, social media has fueled its popularity. In 2019, according to statistics gathered by the official Pilgrim's Office, more than 340,000 pilgrims representing 190 different countries trekked the Camino de Santiago in that year alone. Yesenia and I walked the Camino de Santiago on the "Camino Norte" route across Spain's northern coast. For us, as with the thousands of other peregrinos, the reasons for choosing this pilgrimage were both personal and universal. Personally, the journey was about transformation from my life as a single adult to a married man. Yesenia and I were married on April 22nd, the 12th day of our pilgrimage. We left for Spain as two individuals, and we returned as one. The experience of walking for weeks alongside my partner was as significant and spiritually meaningful as the short walk down the aisle of the church on our wedding day. In this way, the pilgrimage was a way for me to shed my old life and be reborn anew. Photo credit to our wonderful photographer, Luis, at Love Mas Love (www.lovemaslove.com) I want to be careful not to over-romanticize Pilgrimage. It was hard. We averaged 10-15 miles a day. Our longest day of walking was nearly 20 miles. By the end of each day, our feet were swollen and our legs were aching. We spent most evenings rubbing ointments on each other's soles. We prayed that our shoes would withstand the stress and our feet would remain free of blisters. Pilgrimage is a spiritual practice, but the irony is that most moments on our pilgrimage did not feel spiritual; it was quite the opposite, as most moments felt very human. Our skin was, at times, sun-slapped and covered in sweat; other times, it was drenched in rain. We experienced a range of human phenomena, hunger and thirst, weariness and impatience, and longing and satisfaction when we reached our destination. There was a need to use a toilet when none can be found. In this way, pilgrimage is the antithesis of quiet meditation. Instead of sitting still in contemplation, you are on the move, your mind wandering. And then, at once, you snap back to attention when you think you've taken a wrong turn or lost the trail. And yet, through the daily rhythms of the outward journey, something is reborn inside you. Paulo Coelho writes in The Pilgrimage, "When you travel, you experience, in a very practical way, the act of rebirth. You confront completely new situations, the day passes more slowly, and on most journeys, you don't even understand the language the people speak. So you are like a child just out of the womb. You begin to attach much more importance to the things around you because your survival depends upon them. You begin to be more accessible to others because they may be able to help you in difficult situations. And you accept any small favor from the gods with great delight, as if it were an episode you would remember for the rest of your life."11 Rain or shine we trekked forward each days stopping for only one day - the day we got married. The theme of transformation reoccurred in many of the peregrinos we met. On the train from Barcelona to San Sebastian, we sat next to a gentleman in his seventies. He asked us if we were here for the Camino—our backpacks gave it away. We asked him what inspired him to walk the Camino. He told us that he lost his wife of fifty years in 2020. The Camino de Santiago was something they always talked about doing but never did. He was there to walk the Camino for both of them. He questioned if his aged body would be up for the long journey, but he said he knew his wife would be with him. My wife and I traveled to Spain to start our lives together. He traveled there to transition to a life apart. We met an American man in his twenties traveling solo with sunscreen chalked on his face and a camera strung around his neck. He told us that he had spent the last several years working long days in the high-stress world of finance in New York City. He had enough and quit his job. Before making the transition back to to his home in Northern California, he decided to take some time off and reorient himself by walking the Camino de Santiago for five weeks. In his book The Way is Made by Walking, Arthur Paul Boers writes about the paradox of pilgrimage. Is it necessary for one to travel across the world to begin their walk? Why not walk wherever you are? Pilgrimage is, in its truest sense, travel for the purposes of encountering God. So what if people who walk with no religious affiliation at all? Are they "true" pilgrims if they are simply taking a long walk? What about the privilege of pilgrimage?How many people have the resources and time to afford to take weeks out of their lives to walk for the sole purpose of spiritual edification? The majority of Christians in the world will never be able to make a pilgrimage like the Camino de Santiago. Are they somehow being denied some epiphany into the nature of God by staying home? The questions are valid, and I struggle to give a satisfying answer to them. Of course, you can walk where you are, and it would make far less of an impact on the environment. It is true that non-religious people can find meaning in the act of pilgrimage sans any traditional spiritual affiliation, and I don't think that embarking on a pilgrimage is essential for spiritual enlightenment. However, it is important not to devalue the importance of pilgrimage as a spiritual practice. As noted above, there is a Biblical precedent and pattern of God calling people to travel, to walk the long road, often through the "wilderness," to draw nearer to the will and presence of God. In a mythical sense, since humankind's eviction from Eden, humanity has been on the move, searching for its way back to spiritual union with God. Pilgrimage, while not mandatory, can be a way for seekers to create an environment for a divine encounter. As Boers writes, "Pilgrimage is about integration, body and soul, feet and faith".12 On the left: A place to sit and rest welcomes us near this now abandoned ermita. A sign out front tells the story of monk that once lived here waiting for pilgrims to pass by so he could offer them food and rest. On the right: swamps of mud made for slow-going. After 19 days and over 230 miles, we ended our pilgrimage in Oviedo, Spain. From the beginning, it was the plan that we would complete this trek in Oviedo, 193 miles short of Santiago de Compostela. We told ourselves that we would return to finish what we started one day. I couldn't help but wonder if I would be disappointed when we arrived. Would there be an anticlimactic letdown that would leave me regretting that we were not walking all the way to Santiago de Compostela? What if we arrived in Oviedo and I felt no sense of spiritual epiphany? We could have gotten married back home in California with friends and family in attendance. I wondered if this pilgrimage was spiritual vanity meant to puff up my ego. The risk of pilgrimage is the possibility of disappointment. Just as true in the Middle Ages as it is today, there are no guarantees you will find what you think you're looking for on the journey. That is not the point of pilgrimage. The purpose of pilgrimage is not a destination or "arrival" at some point, be it spiritual or physical. The purpose of pilgrimage is to draw nearer to the voice that first called you. In a sense, it is about obedience as much as it is about an epiphany. In the not-so-glamorous rhythms of daily pilgrim life, the heart postures itself toward humility. In the hardship and weariness, one rediscovers his need for a holy other. In the unexpected blessings—the beauty that reveals itself around the bend—one re-delights in divine wonder. After we checked into our hotel and cleaned up, we headed to the Cathedral of San Salvador, a gothic church in the heart of Oviedo. Construction of the cathedral began in the 13th century and concluded in the 16th century. For hundreds of years, pilgrims on their way to Compostela would have witnessed the church's rising. The Holy Chamber, called the Cámara Santa, holds the treasures of the Asturias Monarchy like the Cross of the Angels, a gold-plated and jewel-adorned cross from the year 808. It is said to have been crafted by angels because the craftsman disappeared without accepting payment for the masterpiece. The chamber also holds several religious relics with extraordinary claims: a sandal that belonged to Saint Peter; a splinter from the cross that Christ was crucified on; and dirt collected from the home of Mary, the mother of Jesus. Perhaps the most venerated piece in the collection is the Sudarium of Oviedo, or Shroud of Oviedo. According to church history, it is the cloth that was wrapped around the head of Jesus Christ after his death. It sits protected in a plated ark and is displayed to the public only twice a year. Like the Camino de Santiago, the relics lying in the Cathedral of San Salvador are a mix of history and legend. Regardless of the historicity of the artifacts, the power they hold over the beholder is real. It grips one's religious imagination and kindles the desire that humans have to experience something truly sacred. Gazing upon these relics, I felt connected to the countless pilgrims who went before me. It was a fitting place to end our journey. In a way, our pilgrimage was the Camino de San Salvador. Humans are called to places. There is something in human nature that compels us to travel to sacred sites, to walk the paths toward something mysterious. The desire to connect to someone or something bigger than ourselves is always at work in our psyche, if not consciously, then subconsciously. Today, the Camino de Santiago is less about the veneration of religious relics, penance for sins, or search for miraculous healing. I think it is more about the wonder of an ancient story, our universal longing for sacred meaning, and the healing of our battered souls. The Camino de Santiago is the story of thousands of pilgrims the world round who said yes to a simple human desire. I'll go for a walk, and perhaps I will meet God. Above: The Cathedral of San Salvador Left: The Holy Chamber holds religious artifacts dating back over a millennia. Right: A facsimile of the Shroud of Oviedo hangs above the ark where the shroud rests.

1 Comment

Strolling along the port of Valdez. After a week of traveling solo, I was looking forward to seeing someone I knew. I met Sheri on my Kilimanjaro trek in 2018 and was impressed and inspired by her faith and fortitude on the mountain. When you travel with someone and do an effort like Kilimanjaro, you quickly see past any veneers. Sleep-deprived, cold, and feeling the effects of altitude sickness, you see what people are made of, and Sheri was the real deal. When I told her I was visiting Alaska, she graciously invited me to stay in Valdez with her and her husband. Valdez (properly pronounced "Valdeez") is a small town of around 4,000 permanent residents. It felt fitting to be ending my trip there. Valdez is the terminus of the 800-mile Alaskan pipeline, which I followed for much of my trip. Valdez is unlike any place I've been to. Nestled near the head of a deep fjord in Prince William Sound, the town is walled by glacier-carved mountains and sea. The micro-climate in Valdez produces an astounding 300 inches of snow each year, but with more moderate temperatures than other parts of Alaska. It was amazing to me that early prospectors found the place, let alone built a town there. Valdez has experienced hardships. In 1964, the community was devastated by a massive 9.2 earthquake that lasted a horrifying-to-think-about four-and-a-half minutes and claimed the lives of 32 people when an underwater landslide collapsed the docks in the harbor. After the earthquake, they moved the town 4 miles to the north to build on more solid bedrock. Then, of course, there was the oil spill in 1989 that occurred 25 miles to the south of the port of Valdez, which was my only association with Valdez until my visit. I no longer think of crude oil when I hear the word Valdez. I think of grandiose natural beauty. The town of Valdez quaintly nestled in by mountains and clouds.

On the second evening, Sheri and Todd treated me to dinner theater. The show was an original musical comedy about the history of Valdez. The four-course meal was superb, and the show—surprisingly bawdy—was quite charming. After the show, the venue hosted an open mic. Guys with long scraggly beards on a reprieve from working the fishing boats played their guitars and sang their songs. There was nothing pretentious about it, which made the whole evening enjoyable. No one plays an open mic in Valdez, AK, in hopes that they'll get "discovered." They played because they love music. I was packing up the car to leave on the morning of July 5th, which happened to be my birthday, when Sheri bounced out of the house. "Do you think you can stick around for another hour or two?" I looked at her inquisitively. "I suppose so." "Todd and I want to give you a birthday present. We want to take you on a glacier helicopter tour.” I couldn't believe it. Really?! I accepted the offer. Sheri and I drove to the airport, where the small twin-blade helicopter awaited us. The flight was a little over an hour long, and I enjoyed every minute of it. I sat next to the pilot on our flight out and gawked at the views of the quaint little town and surrounding lush green mountains. Our pilot pointed out black bears and mountain goats along our path to the Chute Glacier. He landed the copter on the glacier, and we spent about 20 minutes exploring the living ice. The whole experience was quite astounding and was one of the best birthday gifts I have ever received. The pilot and I chat about the characters of blue water. Driving from Valdez to Anchorage to catch my flight home, I had hours to reflect on my time in Alaska. I couldn't stay any longer. I mean, I could, but the experiences of the last 10 days filled me to the point of overflow. I needed to leave to process and reflect. I needed to take the sensory input and let it transform into memory and integrate meaningfully into the larger whole of my life experiences. That sounds weird as I write that, but perhaps you'll understand what I mean. This fullness I speak of is a profound sense of satisfaction and wholeness that arises from deep within. It is Boundless Love, and I believe it to be the rarest kind of love. When we think of love, we mostly feel and express it in terms of subjects and objects. I love _____ . And we long to be the object of someone's love. We search for it. We'll settle for it in unhealthy teaspoon portions because our hunger for it is so great. This kind of love can be powerful, but it is nonetheless bounded and will be accompanied by anxiety, fear, and longing. How much of our energy is spent worrying about the things we love? Bounded love will at times feel like bliss, betrayal, hope, lunacy, intimacy, and loneliness. This is because objects like people can fill the heart but not the soul. The soul can only be filled by the ineffableness of Boundless Love.

Our helicopter rises above the clouds in the mountains near Valdez, Alaska.

Mountains accompany nearly every view along the Denali Highway. I had been warned about Denali: "You may not even see the mountain." The warning was not so much a harbinger of foreboding as it was a governor for my expectations. Alaskan weather, often overcast and rainy, doesn't always cooperate with one's itinerary. When I arrived at Denali Park, it seemed that the forewarning would be correct. It was raining. A sigh welled up in my gut. The plan was to camp for two nights, but the idea of camping in the rain filled me with dread. "This is why I am here," I told myself. "It's all part of the adventure, right?" My apprehension lifted when I checked in for a campsite. "We're full tonight," the ranger said. "But there are sites available tomorrow." I looked out the window at the rain assaulting the windows and sighed with relief: "No problem. I'll take tomorrow." I found a room for the night not far from the park entrance that turned out to be just what I needed. I hadn't showered in a couple of days, and my hiking boots were still soaked from biking through foot-deep puddles up in Coldfoot. Also, sleeping in the back of the Jeep, though convenient, was something my back didn't want to do too often. The hotel gave me a chance to clean up, dry out, and catch up on sleep.

After my morning hike, I made my way to the campsite. With my tent pitched and logs on the fire, I settled in. I read the only book I'd brought with me, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes by Belden Lane. “Wild places have always tantalized the human imagination, captivating even as they unnerve…” My plan was to leave Denali in the morning, but a part of me felt that I needed more time there. The beauty was so generous that I didn't want to leave. I'd driven alongside the Nenana River the previous day, and this had given me the urge to get on the water, so I found a rafting tour - an 11 mile trip down the river with class 3 and 4 rapids - and booked it for the next day. When I arrived for my rafting excursion, they zipped me into a dry suit, explaining that the glacier water that fed the river was a very chilly 36 degrees. Without the suit you would become hypothermic within minutes if you ended up in the water, but with the suit, you could survive for hours.

I grabbed dinner at the Prospectors Pizzeria and then hit the road again. It was well into the evening hours, but because of the abundant daylight, there was no pressure to make good time or reach a certain destination by nightfall. I headed south from the Denali Park entrance and then turned east onto the Denali Highway. Like the Dalton Highway in northern Alaska, the word "highway" is used loosely. The Denali Highway is an unpaved route that cuts 135 miles across central Alaska, and let me tell you, it is spectacular. There are many beautiful and scenic routes across the US, but none compare to the experience of driving the Denali Highway. The click-clack-click of gravel hitting the vehicle's undercarriage, the bumps and potholes, and the unevenness of the path necessitate a slowdown. Then, there is the view. "This is Alaska!" I thought to myself. Shrubbery and boreal trees marked the rolling green land that stretched for miles north to the snow-capped Alaska Range. Beneath the peaks, rivers and streams branch like veins of life. Anticipation and its more confident cousin, expectation, filled me. It felt as if at any moment, I might round a bend and see something extraordinary. Humankind, though present, felt dwarfed and insignificant. Here, you are a piece of the Greater, and there is no mistaking that. Coming from Southern California, where the popular camping and hiking locations require permits and reservations sometimes far in advance, I had a hard time wrapping my mind around the accessibility of the land. Along the highway are numerous places to pull off the road. You can camp, fish, and hunt pretty much anywhere (with some restrictions on hunting). The only caveat is that you're on your own. There are few services to assist you. You must act in cooperation with the land if you are to avoid disaster. A view to the north along the Denali Highway. I stopped for the night at the Clearwater Mountain Lodge at mile 80, close to the highway's midway mark. It's a family-run bed and breakfast and one of the few spots along the road with services. I stepped into the Sluice Box Bar, a trailer-sized shack and the most middle-of-nowhere bar I've ever been to, and took a seat. My company that evening was two friends in their 20s from Anchorage who met in the army, the bartender who was a recent college grad from Indiana, and the lodge owner's son. I don't recall what we talked about, but it filled a good couple of hours. At one point, a burly man with a thick beard came in and ordered a Heineken. He told me he was one of the stars of an upcoming NBC/USA Network wilderness survival show. They were about to start production on the Alaska episode. I wished him good luck. The walls of the Sluice Box Bar were covered with dollar bills. I asked the bartender what that was about. "It's an old tradition that dates back to the early prospectors," he told me. When a new prospector would arrive in town with eyes filled with dreams of gold, he would leave a dollar with the bartender. That way, if (or when) the man blew his life savings searching for treasure, he still had a dollar left to his name. He could stumble back to the bar and commiserate his misfortunes over one last drink. I pulled a dollar bill from my wallet, signed it, and stapled it to the wall. Now, I know if all else fails and I go for broke, there is a place in the middle of Alaska that still has a dollar with my name on it, and they are saving it for me. The gas station at the Clearwater Mountain Lodge on the Denali Highway. I slept in the back of the Jeep that night at their designated campground and set out early the next morning. It was another gorgeous blue-sky day. As the Jeep rumbled down the road, I was once again gripped by the land. "Behold," I thought to myself. "Behold? What a funny word." It's a word I would never use in daily life, except maybe around the holidays if I were reciting the Christmas story, but here, it felt right; its utterance is necessary to respond to the moment. Behold. How often do we hold a moment - sit with it or stand with it - ignoring all distraction, and simply allow ourselves to succumb to its grip? I realize there was a reason why the word behold is not part of my vocabulary. It's because most days, I don't stop long enough to let a moment grip me. I reach for the distraction; I seek it. There are occasions of "that's cool," then it's on to the next thing. On the Denali Highway, I rediscovered the meaning of the word "behold." It is a sense of falling into deepness. "Deep calls unto deep," the Psalmist says (42:8). So much of life is spent splashing in the shallows of trivialness when, all the while, the deep beckons us. There is more meaning and aliveness to be felt and experienced, but we must wade away from the familiar shallow edges to get there. We must learn what it means to behold. A morning drive along the Denali Highway provided stunning views. It was sometime around noon when the wheels of my Jeep found pavement again. With just a few days left in my Alaskan journey, I continued south toward Valdez, a small town with a rich history situated precariously between the Chugach mountains and Prince Williams Sound.

The Dalton Highway stretches toward the Brooks Range in northern Alaska The first sign that I was crossing a threshold into a new frontier was the sudden reappearance of light. I was in Seattle. The sun had set, and the sky was that dark navy blue fading to a nighttime black. It was shortly after 10 pm when my flight departed for Fairbanks, Alaska. As the plane reached its cruising altitude, hugging the coastline heading northwest, the sun did the strangest thing; it reversed direction and rose again. You can imagine my disorientation. I was leaving the land of day and night and traveling to a place of perpetual light. I realized that I would need to reorient my vision and let my body loosen its reliance on circadian rhythms. I arrived in Fairbanks around 1 am local time. Sunshine and a "Welcome to Alaska" sign greeted me when I stepped off the plane. I stayed at a hotel near the airport with the curtains tightly drawn. The following day I grabbed a cup of coffee and walked down the shoulder of the highway about a mile to pick up my rental car from Alaska 4x4. An orange Jeep Wrangler awaited me when I arrived. We became friends immediately. She proved to be a good companion for the journey. Though she didn't have much to say, she was dependable and a good listener. I left Fairbanks after stocking up on groceries and topping off the gas tank. My destination was Wiseman, Alaska, population 14, about 270 miles north of Fairbanks (approximately 2,000 miles north of Seattle). To get there, I had to take the Dalton Highway, the haul road made infamous by the TV show Ice Road Truckers. Built in the 1970s, the road provided access for the construction of the Alaskan pipeline, which stretched from Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic Ocean to the port in Valdez, near the Gulf of Alaska. There were paved sections, but the majority of the road was compacted dirt. Fortunately for me, I would not have to traverse the path covered in snow or ice. A lonely tractor-trailer leaves a trail of dust in its path as it rolls up the Dalton Highway.  There was tremendous freedom that came when I turned off the GPS. No voice telling me where to go or when I'd get there. No expectation for arrival. No heads-up on the traffic ahead. The only certainty was my direction: north. Which way the road will bend, I do not know. The peaks and vales between here and there, I will discover when I'm there. How long will it take? Who cares. North. That is the destination, and that was enough. I stopped along the way to stretch my legs and snap a few pictures. I spent some time at the welcome center — a small cabin — near the Yukon River. The host seemed excited to have a visitor to talk to. She gave me updates on the latest wildlife spotted in the area. "Three moose passed here just yesterday." I walked down to the swift-flowing Yukon River and tried to imagine what it looked like 150 years ago when floods of prospectors used the river as a highway to the north. I arrived at Coldfoot Camp in the late evening, though you couldn't really tell what time it was by the sun's orientation. Coldfoot is a trucker's stop and base camp to all things in the arctic North. It is one of the only places on the Dalton Highway where you can get gas and a hot meal. A short gravel runway allowed bush planes to come and go. I spent two nights in a cabin in Wiseman, fifteen miles north of Coldfoot. During the day, I explored the area. I pack-rafted down Koyukuk River and biked local trails, all with an eye over my shoulder and my ears perked for any signs of bears. One morning, I drove 100 miles north through the Brook Range to see the expansive tundra. The permafrost and lack of winter sunshine prevent trees from growing. But during the summer, when light is plentiful, the tundra transforms into a blanket of green grass and wildflowers. Except for the cool temperatures, it doesn't look "Arctic" at all. Rather, it is lush with plant life and birds that migrate from as far away as New Zealand. As the breeze brushed my face, I swear I could hear the voice of David Attenborough say, "Summer in the Arctic Circle is the season of transformation . . . ." Closed in 1956, the Wiseman post office still stands today. To say the mosquitos were thick would be an understatement. I wore a jacket, pants, and a buff around my neck, yet this did not deter the vampire insects from seeking my blood. My only exposed skin was on my hands and bald head. It made for a poor buffet, but they didn't seem to care. The numerous bites on my head inflamed my skin, further agitated by the mesh trucker hat I wore. For several days, it looked like my scalp had some sort of skin disease. My pack raft guide, Dan, was a young man from Western Massachusetts. After googling "remote arctic work," he found Coldfoot and took a job as a guide — Northern Light viewing being the draw in the winter. He appreciates the remoteness and the small, tight-knit community that he found: "It suits me." He lives a simple existence in a small four-walled tent during the summer. His pack of dogs helps him enjoy and navigate the long winters. As I swiped at the mosquitoes buzzing around my face, he said, "Yeah, this place will bite you." It's the mosquitoes in the summer, frigid air in the winter. "It's the price you pay to be here." I was reminded that beauty comes at a cost. There is a sacrifice you must make to experience a place like this. I wondered how many leave and only remember the bite. Dan, my guide, prepares the rafts for our trip down the Koyukuk River. On my last day in the Brooks Range, I took a flight tour over the Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve. This park is the least visited (for obvious reasons) national park in the US. With no roads or trails into its vast wilderness, the only way to access it is by air or to bushwhack by foot. The flight wasn't great if I'm honest. The skies were overcast and the air choppy. The plane was an old 10-seat turboprop that fed my claustrophobic anxiety. When I wasn't wiping my palm sweat onto my jeans, I tried to take some pictures. After we landed safely and I confirmed that I was indeed still alive, I was glad I did it. It gave me an appreciation for the expansiveness of this "last frontier." I walked away pondering: If beauty exists in the wilderness and no one is there to witness it, is it still beautiful? "Indeed," I thought to myself. "For beauty is beauty with or without the eye of a beholder." A look down into Gates of the Arctic National Park. One of the few clear pictures I was able to capture. The plane tour ended at around 10:30 p.m. I didn't have a place to stay that night, so I decided to get a head start on my drive for the next day. I left Coldfoot at 11 p.m. and headed south on the Dalton Highway. I was tired, but the sunlight kept me awake. I listened to the Chronicles of Narnia on audiobook. As the Jeep rumbled down the dirt road, I met almost no traffic for 100+ miles. I had the expanse from horizon to horizon all to myself.

There is that moment during a sunrise when the light first makes its appearance, and the sky turns a purple/violet/pink. It lasts for maybe 10 minutes; then, the emerging sunlight replaces the royal colors. That's what it was like driving down the Dalton that night, but it didn't last ten minutes; it lasted for hours. The combination of fatigue, solitude, and the light of the enchanted sky created this perfect moment of blissful gratitude. A sense of love welled up inside me. For whom or what, I could not say. Just love. I pulled off at a campground at around 1:30 a.m. I was too tired to set up my tent, and then, of course, there was the thought of hungry bears. So, I crawled into the back of the Jeep and slept for the rest of the night. In the morning, I rolled out the back of the vehicle, made a cup of coffee with my Jetboil, and turned my eyes to the south toward Denali National Park. A look at "Thor's Hammer" and beyond in Bryce Canyon National Park My drive from Capitol Reef to Bryce Canyon was one of the most peaceful and enjoyable drives during my road trip odyssey. Perhaps the knowledge that I would end my day in Las Vegas heightened my ability to enjoy the moment. I drove on a quiet highway, passing small towns and valley farms, listening to Aristotle's Poetics on audiobook. At some point, the orange dividing lines on the road disappeared, and the road turned into what we called home a "black-top" or a no-frills strip of asphalt. I consulted Google Maps to make sure I hadn't made a wrong turn. It assured me that I was indeed on the right path to my destination. I settled into the drive and reflected on the preceding weeks, the people I met, the places I visited, and the chance to connect with something beyond, that ineffable something that lifted me from the doldrums. I felt the most profound sense of gratitude. I arrived at the Bryce Canyon Visitor Center and got the last stamp of the trip in my National Parks passport book, then set out to see what there was to be seen. I didn't know what to expect from Bryce Canyon, except when I mentioned it to people who had been there, they all had the same look on their face. It was a look of delight. Their eyes smiled, and their head nodded in knowing affirmation, followed by a, "Oh, you're going to love it." Strolling among the hoodoos Bryce Canyon was one of the biggest surprises of the trip and perhaps the most magical of all the landscapes. It's not a canyon. It is numerous canyons and amphitheaters carved into the side for a forest-covered plateau. The canyons boast the largest concentration of irregular rock columns, called hoodoos, in the world. The towering spires and sandstone walls stand proud and defiant against the elements prone to batter. The rugged beauty of this area is a testament to the audacity of the natural world. As I bopped down the trail from Sunrise Point, I came across another surprise. I noticed a hiker in front of me and further down the trail — a woman with a slight hitch in her step. As the gap between us closed, a thought popped into my head. "It can't be," I told myself. I blinked my eyes rapidly, rubbed my eyes cartoonishly, and looked again. The backpack was the same color, and she appeared to be nursing a sore ankle. "Is that…?" I passed her on the left, trying very much not to be creepy while looking back at her. She stopped in her tracks. "Nathan?!" “Lena?" I retorted, feigning perplexity with my voice. Sure enough, it was her, the hiking companion I met in Arches National Park two days prior. We picked up right where we left off. "How's your ankle?" "What did you think of Capitol Reef?" "No, I won't judge you for wearing the same clothes you were wearing two days ago." The delight of this chance encounter made the land seem more magical. The conversation turned to banter, and we joked about what other hikers were thinking. We took our time strolling the trail, gawking at the scenery, and snapping pictures along the way. We climbed up the Navajo loop trail through the narrow canyon called Wall Street and arrived at the canyon rim at Sunset Point. A decision had to be made. I opted to head back down into the canyon to see a bit more — it was my last day in the wild, and I wanted to make the most of it. She decided it was best not to push her luck with her tender ankle. So we wished each other well and went our separate ways. If life were a Hallmark movie, perhaps the story would not have ended there. But experience has taught me that life is not a movie, and I've learned to say my goodbyes. Except for the exchange of a few text messages, we have not spoken since. I rolled into Las Vegas as the sun was setting. I was greeted enthusiastically by my dear friends, who welcomed me into their home. "How was your trip? Tell us all about it!” I stumbled. Where do I even begin? I thought to myself. How can I possibly explain the journey of these past 40 days? It wasn't just the places seen over the many miles driven. It was over the rugged landscape of my soul that the greatest distance was traveled. After I returned to Los Angeles I wrote this reflection. Journey's End 40 days. 7 states. 9 National Parks. 4,408 miles driven. 110 miles hiked. 1,448 photographs snapped. 60 hours of audiobooks. I drove through 115-degree heat and a snowstorm. I traversed mountains peaks, weaved through canyons, stumbled through deserts, felt wind rumble forests, and watched time float down rolling rivers. I saw numerous bison, elk, deer, and antelope. I met two Red foxes and one lonely rattlesnake. I traveled solo, but I did not travel alone, for I met many fellow sojourners along the way. What was I looking for? I still don’t know. There was no epiphany, only the rediscovery of the many tiny miracles; in each sunrise and sunset; around dusty corner bends; in the smile of a welcoming host; in the chilly air of the starry night sky; in the enduring rhythms of life in a world away from humankind. I encountered the great Silence, and it was divine. A sublime sunset over Yellowstone

Mesa Arch frames the rugged sandstone landscape in Canyonlands National Park I left Arches early on Sunday morning to head to nearby Canyonlands National Park. I entered the park from the north in the "Island in the Sky" district, which is how, I believe, most people view Canyonlands—from above, looking over the landscape's cavernous rifts. To say the area is vast would be too obvious. Words and pictures fail to capture its scope, which invoked a sense of both wonder and frustration. My eyes could not open wide enough to consume the whole of it. Still, there was a desire to draw closer, to descend its water-worn walls, to feel the timelessness more intimately. To access the canyon floor would require a 2–6 hour drive—depending on where you're heading—through the east entrance of the park. I did not have the time for that, so I had to settle for a couple of short 1–2 miles hikes above the rim and a promise to the land: "I'm not done with you," I whispered as I drove away in the early afternoon. The official line is that water and time carved this epic ditch in the earth. I think it looks like God took an ax and split the earth open. I arrived in Capitol Reef National Park in the evening hours when the sun paints the red rock walls with its orange-hued light before retiring for the day. It was a lovely welcome. Capitol Reef stretches nearly 100 miles from north to south along the geologic formation called the Waterpocket Fold. It's basically a lift—or monocline—in the rock layers of the earth's crust that occurred during a "big event" 50-70 million years ago. An ancient fault lifted rock layers on the west side more than 7,000 feet above the rock layers on the east side. Over the millions of years that followed, ongoing erosion carved and crafted its novel and colorful formations and canyons. "Follow the light" On the road into Capitol Reef National Park While the park runs north-south, the only highway that enters the park runs east-west. The park's scenic northern and southern districts can only be reached via dirt roads that require high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicles. I had one full day at the park. The allure of being in a place that so few people visit enchanted me, so I arranged for a guide to take me, via a suped-up Jeep, to the Cathedral District in the north end of the park. My guide was a friendly young man, perhaps in his late 20s. A Utah native, his heart and love for his home state was evident. He worked for the park service as a guide most of the year. During the offseason, he lived simply, often on nearby BLM (Bureau of Land Management) land camping out of his truck. We turned off the highway onto a sandy path that led to the wind- and rain-chiseled sandstone cliffs that reminded early settlers of the flying buttresses of gothic cathedrals. My guide snapped this picture of me as we explored the "Temples of the Sun and Moon" What struck me, beyond the alien formations of the land, was the silence. City-living is a cacophony of noise. You can't escape it. But here, with the car engine off, without wind, animals, or movement, and void of the rhythms of life's sundry sounds, there was a marvelous stillness. My deafened ears grasped for a note to reassure me that my sense of hearing was still functional. In this kind of deep silence, you become aware of an otherness—that thinly veiled something that is always there, but we are unable to grasp in the commotion of life's comings and goings. It is the sense of infinitude, the everlasting and boundlessness of life that sits just beneath the surface of our everyday experiences. "Am I still on planet earth?" My guide explained the differences in rock layers—basalt, sandstone, shale—and I nodded my head like I understood what he was talking about. We traversed the wild landscape for six hours, and since it was just the two of us, the conversation spanned the whole spectrum of topics. We reviewed our favorite movies and shared religious philosophies while touching dinosaur bones and ancient lava flows. When I retired to my room for the night, I felt a bit of melancholy. It was the eve of the final day of my 40-day adventure. The next night, I would return to the bright lights and swirling sounds of civilization. But before I got there, I had one last stop to make— Bryce Canyon. A look down at the "flying buttresses" of the Cathedral Valley, a place where the silence is numinous.

A view (from afar) of Delicate Arch in Arches National Park. I arrived in Moab, UT, on Friday, September 25th. It was the start of my final week of travel. There was a feeling of heaviness hanging over me, an anticipation that soon I would have to return to my life quarantined in the city. This feeling was countered by the excitement of being in Southern Utah and about to visit four National Parks that appear in pictures to be nothing less than magic. I was up pre-dawn on Saturday to get an early start into Arches National Park. It is one of the most popular National Parks in the country, and I understood that parking could be challenging if you delay your arrival. It also allowed me to catch the sunrise over the 2,000-foot red cliffs that towered above the Colorado River near the lodge where I was staying. One cannot predict when Beauty will come for you. It can sneak up on you in the melody of a song or the lyric of a poem. It can come in a warm smile or the casual touch of a reassuring hand. You know it because its appearance has a momentary effect of paralysis. You simply cannot leave its presence until it is done with you. The sunrise that morning was so beautiful, so magnificent, that I could not walk away. Lost in the sight of the sun's coming—a daily happening, I remind myself, that I so rarely witness—that it delayed my departure for the park. First glimpse of an immanent sunrise near Moab, UT. Beauty arrives in a sunrise near Moab, UT. Eventually, I did arrive at the trailhead for the most iconic arch in the park, Delicate Arch, and to my disappointment, the parking lot was already full. I had to take in a view of the arch from a distance, entrusting the zoom on my camera to bring me closer. I didn't linger but decided to move on and head to the Devil's Garden Trail, hoping that I would have better luck with parking there. Good fortune awaited me as I did snag a parking place and quickly threw my daypack over my shoulders and set out for what would end up being about a 10-mile hike. Once away from the crowds, Devil's Garden Trail via Primitive Trail was exactly what I was looking for. The trail led past wind-sculpted stone arches and towering monoliths and provided a sense of mystery and wild wonder.

It was nice to have someone to experience the park with. It provides a different perspective. You notice things you would have missed. She said, "This is my favorite arch." I asked why, and she shared what she saw that I didn't, and my point of view changed. That is what a good travel companion does and why they are so hard to find. They do not divert attention from the experience but add to it and make it more rewarding. They give you a way of remembering a place that isn't based solely on one's own subjectivity. Perhaps our conversation was too comfortable that we weren't paying enough attention. I watched helplessly as she took an awkward step on loose sand and fell to the ground. There was a popping sound, and I could tell immediately that she was in a great amount of discomfort. She grabbed her ankle and grimaced. I asked her if she was OK. "This happens sometimes. I have weak ankles," she replied. I think more than being in pain, she was embarrassed. We were back on the main trail with significantly more foot traffic. The first park ranger we had seen all day appeared seemingly, almost magically, out of nowhere and asked if we needed to be evacuated. "We? Oh, I'm not—we're not. We just met 45 minutes ago." I thought to myself, then quickly determined that trying to explain wouldn't be helpful. I realized that anyone passing by was likely to assume we were together and that I would need to see this through to the end. She insisted that an evacuation wouldn't be necessary. She wrapped her ankle, slid her foot back into her boot, and climbed to her feet. Fortunately, we were less than a mile from the parking lot, and the trail at this point was fairly flat. We took our time walking back. She required no assistance from me, but I stayed with her because I thought the company might take her mind off any physical pain. I asked her what she would have thought of me if I had left her on the trail. She said she wouldn't have blamed me, and we had a good laugh about how nutty the situation was. When we got back to the parking lot, I gave her my number and told her that if her ankle got worse and she needed some help, she can give me a call. I thought I'd never see her again, but in just a couple of days, I would be reminded that life is full of surprises. A short walk down into the "Park Avenue" valley offers an immersive view of towering walls and monoliths.

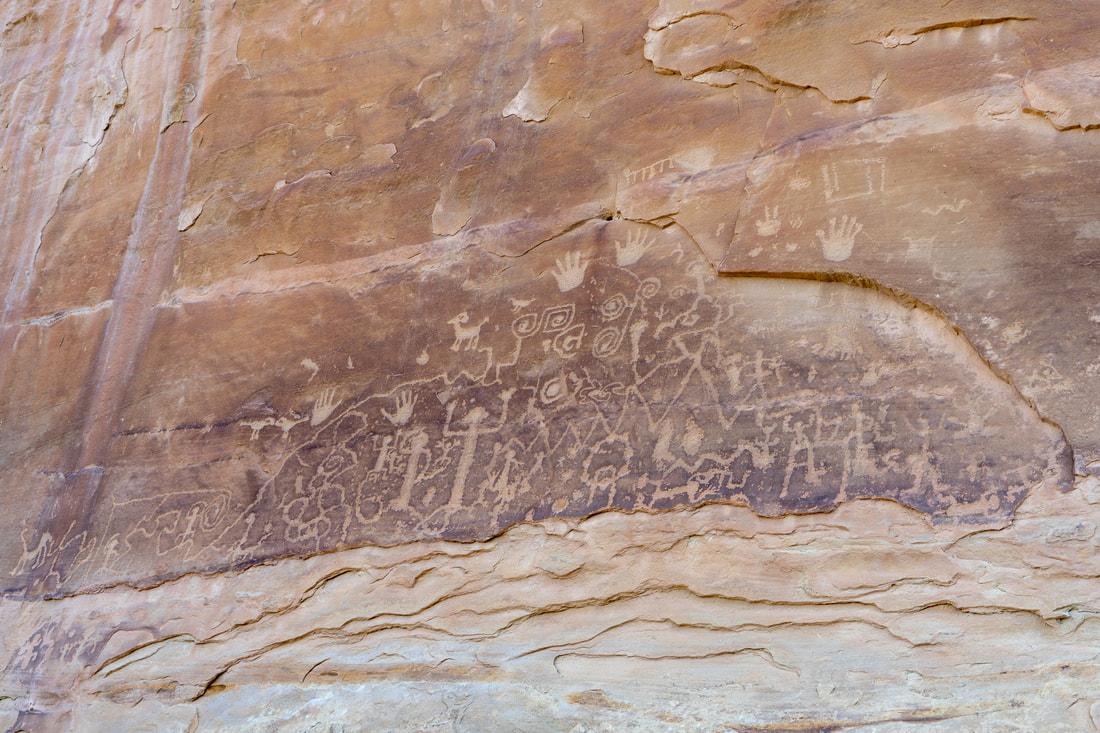

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park I bid adieu to the tiny house by the creek to continue by trek south to Durango, Colorado, but before leaving Montrose, I decided to check out Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. It was a short drive outside of town, and I was curious to see what this park—which I had never heard of before—was all about. My only expectation was that there would be a canyon, and perhaps it would be black. There is nothing that prepares a person for the sense of infinitude that comes when you first catch a glimpse of a deep place like Black Canyon. Your senses are overcome. Your eyes do not know how to communicate to the brain what it's perceiving. Your breath is held captive in your lungs until you remind yourself to exhale. In that spark, the brain sends a pulse through the body that makes the hair tingle on your arms and your spine shutter. The mind asks, "Is this real?" Black Canyon provided this unexpected thrill. Though not as popular as other national parks, it is none-the-less a spectacle. I drove the rim, stopped at several overlooks, and put my camera to action. I knew there was more to see at Black Canyon, but after a couple of hours, I felt I needed to get back on the road and continue onward. It was a picture-perfect September day. Though not peak foliage, autumn's transformation had begun, which made for a colorful drive to Telluride, where I stopped for lunch. Telluride is postcard charming. Cornered by mountains to the north, east, and south the town felt isolated—maybe even protected—from the outside world. I understand why rich people want houses there and why vacationers flock there. I attempted to walk off my heavy lunch in the central village area before grabbing a cup of coffee and hitting the road again. I traveled south on U.S. 550, also known as the Million Dollar Highway, between the old mining towns of Ouray and Silverton. U.S. 550 is considered one of the most beautiful roads in America, and after driving it, I agree. I stopped in both Ouray and Silverton and at multiple turnouts along the way. The mountains in the San Juan Wilderness flaunted colors that I have not seen anywhere else, and the relics of the old mining railroad scattered along the way aroused my curiosity and imagination. Did the miners of the past feel the beauty of these hills, or did they only see what resources could be taken from them? Everyone needs to make a living, but just the same, everyone needs to feel alive. Is nature's purpose to pad the pocket or to heal the soul? San Juan National Forest along the Million Dollar Highway. Railroad relics leave behind tracks of a bygone era. A old mining house abandoned in the shadows of time. I spent the night at a cozy bed and breakfast in Durango. It gave me not only a good night's sleep but also a boost of youthful invigoration as I was the only one there under the age of 60 (from what I could tell). I arrived at Mesa Verde National Park mid-morning, keen to visit this UNESCO World Heritage Site. I had read in National Geographic about the cliff dwellings of the Ancestral Puebloans, so I could not pass on the opportunity to see the archeological sites with my own eyes. Due to COVID restrictions, visitors could not tour the dwellings, but I could still observe them from a distance and hike the trails around sites. Cliff dwellings of the Ancestral Puebloans in Mesa Verde National Park. c. 1200-1300 CE After my hike, I took an audio tour of the area, stopping at a dozen of the nearly 5,000 known archeological sites in the park. I could not help but ponder how wrong we got the native peoples of America. When we saw their arrows, headdresses, and rituals, we thought they were "primitive" or "savage." Yet, I look at the homes they built and the cliff dwellings they inhabited, and I see engineers and architects. For 700 years—long before European settlers arrived in the Americas—they lived, adapted, and survived in this harsh environment. The creativity and savviness of these people are astounding if we don't get hung up on cultural and worldview differences. It still remains a mystery as to why the Ancestral Pueblo people left the area around 1300 CE. Some hypothesize that it was environmental changes that drove them away. Others say it may have been social conflict or political threats. I can't help but think that maybe they just wanted to move on. Perhaps they caught a bit of wanderlust. Or maybe it was that very universal and human hope for a better life somewhere new. Petroglyphs tell the story of a past people who once lived and left their mark on the world. A statue dedicated to the Ancestral Puebloans welcomes guests at the Mesa Verde National Park Visitors Center.

View from the Continental Divide on the Cottonwood Pass I left Cheyenne on a Saturday and drove south into Colorado. I was starting week five of my journey, and I had been pretty much by myself up to this point. When Jen, a good friend of mine from my Boston days 15+ years ago, heard that I was on this road trip, she invited me to stay with her family in Evergreen, CO. After a month of conversing with strangers, I was very much looking forward to connecting with someone I knew. It was a tad strange to be back in an urban area. Driving through Denver, I thought, "I remember this." The traffic, the noise, the pace of movement, it was all familiar. I stopped for lunch at an outdoor suburban brewery. College football played on the TV monitors as I downed a Hefeweizen and BBQ pork sandwich. How quickly the wild retreats when one re-enters the civilized world of shopping centers, parking lots, and microbreweries. I had both a feeling of comfort and loss. I missed the city-dwelling life before the pandemic—the ability to satisfy any taste of the palette, and the bustle of the city with its ample distractions. It felt good to be back; yet, as tempting as it was, there was also a part of me that wasn't ready to return. The wilderness wasn't done with me yet. I enjoyed my time with Jen, her husband, and two kids and welcomed their generous hospitality. We drank lots of wine and laughed as we reminisced about the old days and how our lives (and the world) had changed since then. I couldn't help but think that I was peeking in on what my life could have been. Somewhere in the hypothetical multiverse, there is a version of my life where I am married, raising kids in a suburban neighborhood, in a beautiful place like this. This vision is not a bad one at all. There was an allure to it that made me wonder if I had made the right choices in my life. To be 41 years old, still single, still chasing something that I have yet to find. Why? What was it all for? Hiking in the Mount Sneffels Wilderness I stayed in Evergreen for a few days, then left on a Tuesday morning. From this point forward, I disconnect entirely from work, taking vacation days for the remainder of my trip. When I was planning this trip, a friend of mine from Colorado urged me to spend time in the state's southwest region. "You won't regret it," he promised. He was right. I took the scenic 285 S toward Buena Vista, CO. Along the way, I listened to Thich Nhat Hanh's book Old Path White Clouds about the life of the Buddha or "the one who is awake." As my eyes followed the road ahead, I determined that my life had been void of two-lane highways for too long. If I never saw another freeway, I think I could be content. In Buena Vista, I picked up the Cottonwood Pass (route 306) for a stunning drive that topped out at over 12,000 ft as it crossed the continental divide. I stopped several times for pictures, a stretch of the legs, and to simply pause and take in the vastness of the stoic landscape and the moodiness of the cloud-whipped sky. I arrived in Crested Butte, an old mining village turned charming resort town, in the late afternoon and had lunch at a pub on Elk Avenue. I did a little shopping and then continued on to Montrose, where my creek-side "tiny home" Airbnb awaited me. Welcome to the "tiny house" The next day I met up with another good friend of mine. I first met Becca eight years ago, when she led the trip I was on to Indonesia. We connected again a couple of years ago in Tanzania when she led my Mount Kilimanjaro trek.

I met Becca in Ridgeway, and we headed to the Blue Lakes trail in the Mount Sneffels Wilderness for a day of hiking and fly-fishing. Multiple times on the trail, the path would bend and open to a vista that stopped me in my track as I uttered, "My God." The beauty of these lofty mountains was enough to leave me nearly speechless. Unlike my fly-fishing attempt in Wyoming, we each caught several fish and, as gently as possible, released them back to the lake. On the trail, we talked for hours about travel, faith, and social justice. We finished the day bouncing down the dirt road in her four-wheel-drive SUV singing 90s hits, then downing beer and pizza back in town. It was one of the best days of my entire trip. I left Yellowstone on Labor Day, exiting the park's northeast corner at the Cooke City-Silver Gate near the Wyoming/Montana border. It was a quiet drive. I listened to Plato's Symposium on audiobook and made a few stops to hop out of the car and snap pictures of the bison herds hanging on the side of the road. A grey ceiling of clouds appeared just outside of the park entrance, and the temperature began to drop. I was expecting a rainy journey to Billings, but the drive turned into more of an adventure than I anticipated. I noticed most of the traffic, what little there was, turning right on Highway 296 and going around the mountain range that stood between me and my destination, but Google Maps had me staying on Highway 212, the scenic Bluetooth Highway and a more direct route. As I ascended the pass, a blanket of clouds swallowed the road with light rain to accompany it. The scenic byway was not scenic at all, as the only thing I could see through the fog's milky haze and the red glow from the taillight of the truck in front of me. The temperature continued to drop, and the rain turned to snow as the road climbed past eight, nine, then 10,000 feet of elevation. It was one of those driving situations where there is nothing you can do except keep going. Just two weeks prior, I was driving through 110-degree heat; now, I'm in a whiteout snowstorm. Fortunately, after I reached the summit and began the descent, visibility improved. I stopped for lunch in Red Lodge, Montana, with wet snow continuing to fall. I asked my waitress at the pizza parlor about the weather. She shrugged her shoulders and said, "It's September. It happens." I arrived in Billings in a steady downpour. I tried to check into my Airbnb; however, I discovered, much to my surprise, that it was still occupied. I talked to the host, who said the previous guest had refused to check out, and he wasn't sure what to do. I ended up in a hotel that night and arranged to move on from Billings to my Airbnb in Sheridan, Wyoming, the next day. My time in Sheridan, which was eight days in length, was my most prolonged stay in a single place for the trip's duration. I had a private bungalow that was attached to a quaint country home. The homey location was perfect for my needs, and it was refreshing to stay in one place for an extended period. Hiking Tongue River Canyon in Bighorn National Forest near Sheridan, WY My host in Sheridan was a friendly all-American family. Ben and Sarah were native Wyomingites with four kids from elementary to high school age and a pack of sled dogs they raise and race for sport. One evening, Ben invited me to join him when he fed the dogs, and I eagerly accepted. The dogs were full of energetic spirit, and it became apparent to me that these dogs lived for one thing: to run. I was envious of the wild simplicity of their lives; their purpose transparent, and their joy so pure. Feeding time for the dog sled team When I wasn't working, I explored the area. I perused the Western and American Indian art at the Brinton Museum. At King's Saddlery, I daydreamed about quitting my job and becoming a cowboy. I hiked the canyon trails in Bighorn National Forest. While driving around Sheridan and the small towns surrounding it, I noticed something that piqued my curiosity. All of the schools in the area were immaculate, at least from the outside. One evening, I asked Ben about my observation. He said that all the public schools in Sheridan were Blue Ribbon schools. I asked him what drove the economy that allowed such investment in public education. "Energy," he said. The big energy companies have mined the area for decades, providing jobs and tax revenue to fund schools and infrastructure. Living in Southern California for fifteen years, I've seen the impact of climate change: longer heat waves, less rain, snowmelt earlier in the spring, devastating wildfires that are becoming more and more frequent. California has resources to combat the negative impacts of a changing climate, but many places in the world do not. We hear about the wildfires in California (or Australia—those poor, cute koalas), but less about the extreme weather taking lives and ruining communities in the Philippines, Myanmar, or Pakistan. The human impact on the climate must be addressed. However, my time in Sheridan reminded me that there is a human impact on both sides of the climate debate. The economies and livelihoods of many communities are dependent on current resources—coal, oil, gas—of energy consumption. These communities must be included, not excluded, in the climate change conversation and the transition to clean energy. After my stay in Sheridan, I drove down to Cheyenne, where I stayed at an Airbnb that was more like a hippie hostel on a ranch. Upon arrival, I was instructed to enter the house, remove my shoes, spray myself with COVID spray, then make myself at home. The secret ingredients in the COVID repellent were moonshine, witch hazel, and essential oils. It was tongue in cheek, but I obliged. It was 2020, after all, and I was willing to try anything at this point.

|

AuthorA WRITER AND TRAVELER KEEPING THE FAITH IN LOS ANGELES Subjects

All

Archives

August 2022

© 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed